When 'Fake News' Was a Force for Good

“Agents of Influence” sets the record straight on the man called Intrepid

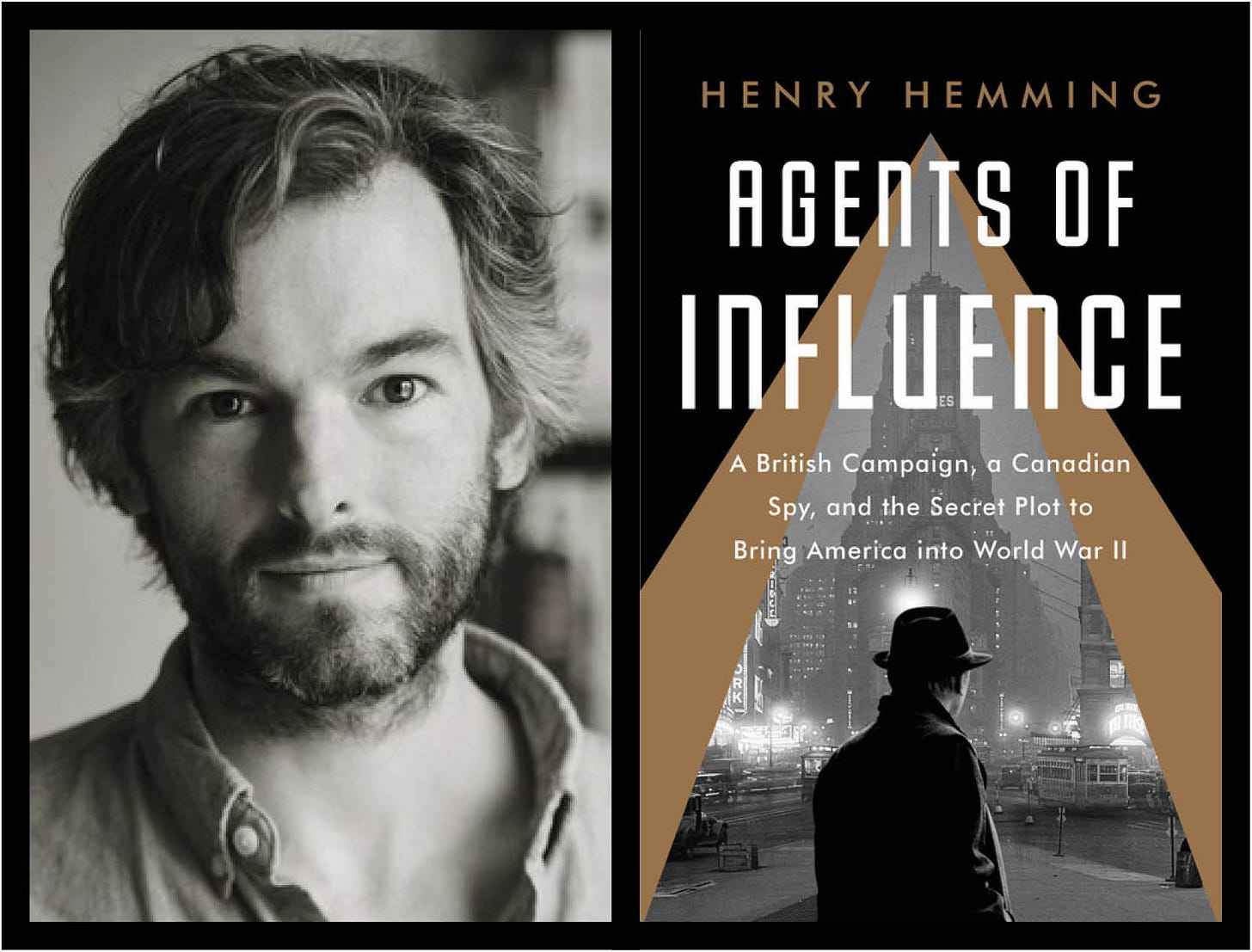

Agents of Influence is Henry Hemming’s engagingly reported story about an audacious British clandestine propaganda campaign to draw the United States into World WarTwo.

On one level, it’s a story of the life and times of William Stephenson, a Canadian with no espionage training who becomes Britain’s unlikely key operative in the United States as well as …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to SpyTalk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.