What Went Missing in “Missing,” the Acclaimed Film on the Murder of an American in Chile

A new book reexamines the facts behind the deaths of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi during the 1973 coup

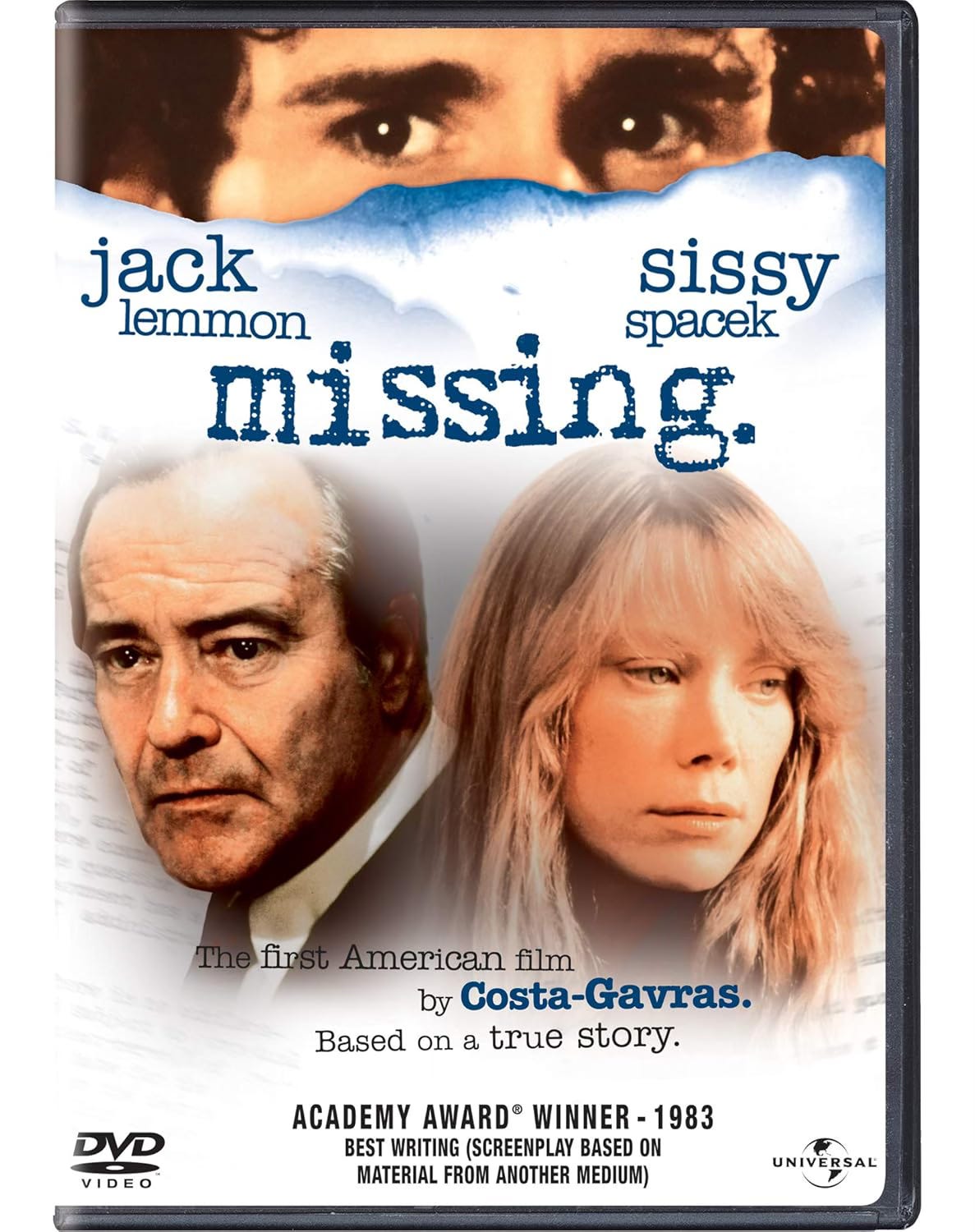

Editor’s Note: In 1982, a feature film based on events following a military coup in Chile debuted to critical acclaim and went on to dominate the Academy Awards. Missing, directed by Kostantinos Costa-Gavras, implicated the U.S. government in the disappearance and death of Horman, portrayed as a somewhat apolitical young American living in Chile during the government of Salvador Allende, the Chilean president overthrown in the U.S.-backed 1973 coup.

The suspicion of U.S. involvement became a kind of official story of Horman’s death, as well as that of the other American who was executed, Frank Teruggi. Missing portrayed Horman as the man “who knew too much” who was killed because of something he learned in encounters with U.S. military officers in the port city of Valparaiso.

But John Dinges, himself a young journalist in Chile during the coup and its violent aftermath, uncovered circumstances and facts of their cases that contradict the widely accepted version. In this excerpt from his new book, Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup, Dinges recasts Horman’s encounter with U.S. officers on September 11, 1973, the day of the coup….

AT THEIR BEACHSIDE HOTEL in Viña del Mar, Charlie Horman and his friend Terry Simon woke up to a Chilean world turned upside down. There was less violence in nearby Valparaiso than in Santiago, and in Viña’s tranquil streets even fewer signs of the military takeover. Stuck in a hotel with people they assessed as upper class and —worse—affiliated with the U.S. military, their guard went up. During the five days before they were able to return to Santiago, they met five American officers, including Captain Ray Davis, the chief of the U.S. Navy mission in charge of liaison with the Chilean Navy, and his deputy Marine Corps Lt. Col. Patrick J. Ryan. Davis was also chief of the U.S. Military Group [MilGroup] in Chile, which was the U.S. embassy’s office in charge of military sales, aid and training for the host country. Charlie and Terry presented themselves as a couple of stranded tourists and were careful not to betray any hint of their pro-Allende sentiments or the devastation Charlie was experiencing about the demise of the Chilean experiment he had invested so much in.

According to a later report by Captain Davis, Charlie said he was living in Santiago and working in a Chilean film company PROA on an animated film for children—a reference to the Sunshine Grabber project, based on a children’s book he wrote. Terry said she was on vacation from her job in New York as a writer for a teenage magazine. Horman’s self-description to Davis was understandably somewhat adapted to his audience. Horman worked in film but his main project was an intensely political documentary on Chile’s fight against imperialism. Horman was guarded, presuming with good reason that the U.S. military personnel he met supported the coup, and he suspected they might even have been directly involved with the actions of the Chile Navy. U.S. hostility toward Salvador Allende’s socialist project was well known, and the United States had a notorious history of military intervention in Latin America. Horman was well read in past U.S. actions such as the instigation of military coups in Guatemala in 1954 and Brazil in 1964.

Horman and Simon suspected they may have happened upon a nest of U.S. co-conspirators in Chile’s coup. The first American Horman and Simon met was Arthur Creter. Horman approached him on the hotel veranda and asked to borrow his newspaper. Creter began to talk freely. He introduced himself as a retired Marine lieutenant currently working as a civilian engineer for the U.S. Naval Base in the Panama Canal Zone. Simon thought she was hearing something important. She reproduced the conversations with Creter and other officers in detailed contemporaneous notes.

[Simon] Been here long?

[Creter] No, just down here to do a job.

[Simon] What kind of job?

[Creter] With the Navy.

Terry Simon added to this exchange in an article she wrote for her magazine, Senior Scholastic, shortly after returning to the United States. “I was invited here by the military. You see, I work for the U.S. Navy. Now my job is done here and I’m just waiting to get out.”

Simon noted that Creter “claims that the coup had been a very smooth operation [and that he] had already talked to Panama by radio.” He claimed to know that “around 4:30 in the morning of the 11th the military began mobilizing, and soldiers placed on street corners throughout the country and [quoting him] ‘about a half hour later all Chile was under military control.’”

In a conversation with an attractive young woman, Creter seemed to be bragging about inside knowledge of how the coup had happened. Creter’s account may have been impressive in the moment, but it was far from accurate, let alone based on exclusive information from Panama. Later documented accounts of the coup events demonstrate that Santiago, for example, was not under military control until well into the afternoon of September 11, and the military was still attacking worker controlled factories on September 12 and 13. In Valparaiso, the Navy did not declare martial law until 7 am.

In a later New York Times article—and in the movie— Creter’s statement about his work in Chile was cast in a more sinister light: “We came down to do a job and it's done.” In the environment of suspicion of the moment, it was widely—but misleadingly—quoted as proof of U.S. involvement in the military coup.

U.S. Navy officials later specified that Creter was hired by the U.S. Navy to come to Chile to work as a “MAP maintenance adviser,” and that he was a “shipboard technician,” and had nothing to do with the coup. Creter did not deny making the statement, but said its context was his job with the U.S. Navy and that he was not talking about the political situation.

Lt. Col. Pat Ryan met and talked briefly with Horman and Simon on September 11 when he came to the hotel to check on Creter. He saw them every day during their stay and drove them into Valparaiso to check at the Braniff Airways office for possible flights. There were none.

They went with him to the U.S. naval mission office and met Lt. Commander Roger Frauenfelder, who talked to them at length. He described the U.S. part of the scrubbed UNITAS joint maneuvers, saying the fleet had arrived with two destroyers, two escort ships and a submarine.

“Says UNITAS was cancelled, that, ha ha, that was one of the tricky things the Chileans did so that no one would know this was happening,” Simon wrote. Frauenfelder said he had been stationed in Chile for two years and in that time “I’ve become a real supporter of the [anti-Allende] cause.” Frauenfelder pointed out his office window to an elegant four masted ship in the harbor. He said the deposed mayor of Valparaiso was being held prisoner aboard the vessel. The ship was the Esmeralda, a tall ship used for training which became infamous when it emerged later that more than 100 political prisoners had been held on board and many reported they were submitted to torture, including electric shock.

Ryan then took them to Chief Paul Epley’s house, where the Naval Mission’s only radio was located. Simon dictated an airgram message to her parents in Waterloo, Iowa, saying she was all right. They had lunch at Ryan’s house and met his wife Audrey. He advised them it might still be risky to return to Santiago, but Simon wanted to make sure she was able to get a flight home as soon as the Santiago airport was opened. In that case, Ryan said, he could arrange transportation in a military vehicle back to Santiago. Ryan said his boss, Captain Ray Davis, had arrived that day to check on the Navy Mission and planned to return to Santiago the next day.

Ryan also made comments about the situation in Chile that displayed his fervent anticommunism. He said he had served several tours in Vietnam and blamed Cuba for what was happening in Chile. He also said that, according to his information, between 1,500 and 3,000 people had already been killed in Santiago. Such numbers were indeed circulating in U.S. intelligence reports at the time, but they were not correct. The real number was 275 people killed or disappeared as of September 14, when Ryan was speaking. He joked about the pilots’ aim in the Hawker Hunter attack on La Moneda, the presidential palace in Santiago. “You’d have to be a real hamburger to miss with a rocket,” he said.

Terry Simon’s notes reflect her strong suspicions, but she acknowledged the military men were friendly to her and helpful. On Saturday Ryan picked Horman and Simon up at the hotel and said their ride to Santiago with Captain Davis was all set. He invited them for a farewell lunch at a local restaurant, The Yugoslav Mansion, where they joined an informal gathering of Frauenfelder and his wife and children and Commander Edward Johnson and his wife Corki, whom they were meeting for the first time. Ryan continued to insist it would be safer for them to stay in Viña. Johnson even offered to let them stay in the spare room in his house. But they said they would take the ride with Captain Davis.

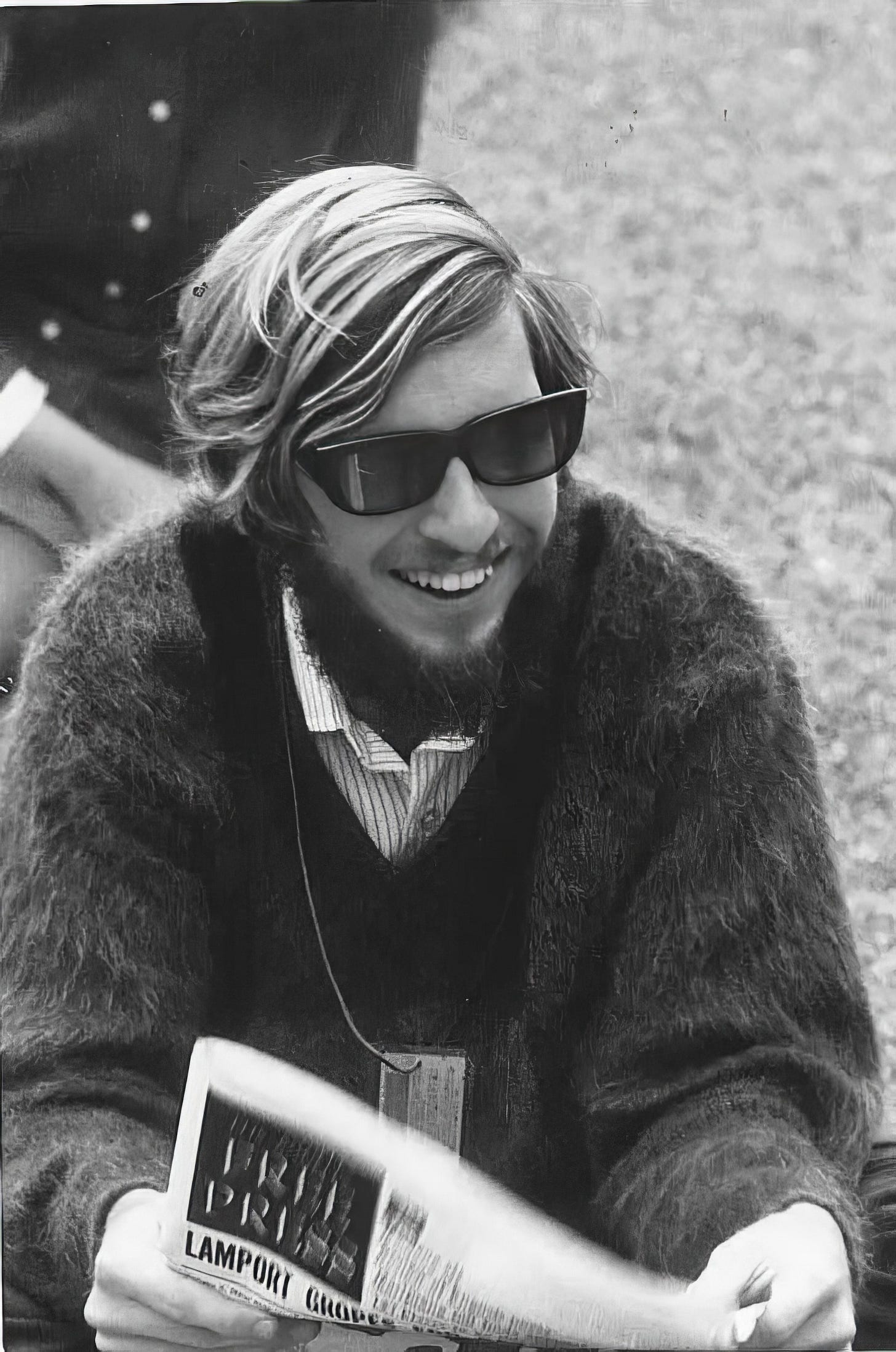

The 90-mile drive to Santiago on Saturday September 15 was tense but uneventful, according to Simon. It was Charles Horman’s only meeting with the man later accused of setting up his murder. Davis chatted mostly with Terry, since Charlie chose to ride in the back seat. Davis deflected her questions about the coup. In Davis’s account of the ride later to his superiors, he noted that Horman mentioned his work on a children’s film. Both his passengers were “well cultured,” but he was most impressed by Simon, who he said “asked numerous and good questions.” Horman had long hair and a beard but was “neatly groomed.” There were few cars in sight as Davis drove them up the steep winding road from the coastal city, past the groves of majestic Chilean palms, and navigated the hills and curves leading to Santiago. Davis dropped them off outside the U.S. Embassy on Agustinas Street about 5 pm.

Downtown Santiago, in contrast to the placid environment they had left behind on the coast, had the fearsome aspect of an occupied city. The bombed out La Moneda Palace was just around the corner from the embassy, at the far end of the large Constitution Plaza. Soldiers manning gun emplacements guarded the intersections. The smell of explosives still hung in the air.

Horman took a taxi to his home in the outlying Vicuña MacKenna district, near a belt of worker-controlled factories known as the “Cordón.” A lot had happened in the neighborhood since September 11, almost all of it disastrous for the workers movement Horman had taken risks to support. The area surrounding Horman’s house was still the scene of ongoing military operations, with squads raiding factories and detaining hundreds of workers.

On Monday September 17, three days after his arrival, Horman was detained in a targeted raid of his house. His unidentified, bullet riddled body arrived at the morgue the next day, around the same time as a group of six union leaders from a nearby factory. Horman would remain “disappeared” for a month.

Decades would pass before the facts emerged: Far from apolitical, both Horman and Teruggi had intense political commitments, and Horman was raising money in the United States to buy weapons to defend the worker-controlled factories that were at the heart of the Allende revolution. #####

Get the whole story here, in Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup

John Dinges, a SpyTalk contributing editor, lived in and reported from Chile during its most violent period (1972–78). A special correspondent for the Washington Post, and later managing editor at NPR, he is Professor Emeritus of Journalism at Columbia University. He is also the author of The Condor Years: How Pinochet And His Allies Brought Terrorism To Three Continents and other books on Latin American dictatorships.