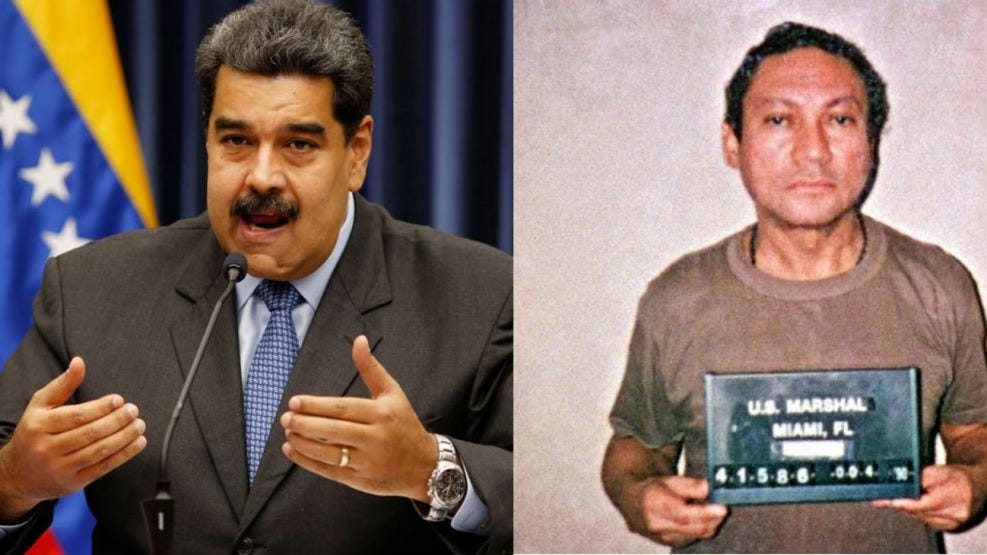

Trump’s Venezuela Rhetoric Echoes Bush Sr’s 1989 Push to Oust Panama’s Noriega

Like Trump and Maduro, President H.W. Bush exaggerated Noriega's drug trafficking to mask other, more base, motivations

President Trump ratcheted up his pressure campaign against Venezuela on Wednesday, announcing that the United States had seized a “very large” oil tanker off the Venezuelan coast. “Largest one ever seized, actually, and other things are happening,” Trump declared. It was a dramatic escalation in the months-long confrontation between the two.

As the president searches for a saleable pretext for attacking Venezuela and overthrowing its leader, Nicolas Maduro, the United States is approaching a largely forgotten anniversary that helps explain what is happening: the Dec. 20, 1989 invasion of Panama.

Throughout 1989, President George H.W. Bush hunted for a justification to launch military action against a sometime U.S. ally, Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega, the strongman of Panama. Trump has been following a similar playbook toward Maduro. In both instances, the presidents faced an authoritarian thug who was, in fact, persuasively charged with crimes: Noriega was eventually convicted of drug trafficking; Maduro is under investigation by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity. But in both cases, the issue of their crimes was a convenient distraction rather than the true policy driver.

The challenge for both presidents was a genuine casus belli—an immediate threat to national security. Bush, who already had U.S. military units stationed in bases in and around the U.S.-controlled Canal Zone, eventually seized on dubious pretexts--including a rhetorical “declaration of war” against the U.S. by Noriega. In fact, there was no such declaration. Panama’s National Assembly had passed a resolution in which it said a state of war “exists” because of U.S. actions. Bush also used the killing of a civilian-clad U.S. Marine lieutenant whose car ran a Panamanian checkpoint a few days before the invasion to say Noriega was endangering Americans.

It remains to be seen whether Trump’s seizure of the oil tanker—Maduro has called it piracy—will provoke a military response from the regime. So far, Trump, lacking even a vague armed response from Maduro to exploit, has resorted to a fabrication: the claim that Maduro is flooding the United States with cocaine with the goal of killing Americans. This, too, mirrors Bush’s playbook for Panama. Bush claimed he invaded the isthmus “to safeguard the lives of Americans [and] to combat drug trafficking.” What went unmentioned was the real reason for invading Panama. High-ranking military and civilian dissenters in the administration said Bush used Noriega and the invasion for his own domestic political goals—to appear to be a strong, decisive leader. Albeit unfolding in a smaller theater than Southeast Asia, it was a deception comparable to the false claim by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964 that North Vietnamese gunboats had attacked U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin, which LBJ used to justify an escalation of American involvement in the war.

In the years leading up to the Panama invasion, Noriega had become a convenient foil for Bush. By the mid-1980s, Noriega—a long-time CIA informant—had backed away from supporting Bush’s master plan to fight Nicaragua’s Marxist Sandinistas and rebels in El Salvador. Noriega had refused to allow the United States to use Panama as a staging ground for military operations in Latin America, or to train for such action at the Panama-based School of the Americas. That refusal, more than any drug charge, made him a liability. Bush became hell-bent on military action to oust him, even when presented with non-lethal options that could have achieved the same result without bloodshed.

Just as Bush falsely claimed Noriega was threatening American lives and the Panama Canal, Trump now cites drug trafficking as his primary motivation for regime change, contending that a Maduro-led cartel is flooding the U.S. with fentanyl. This is a lie. U.S. narcotics experts and intelligence agencies report that the vast majority of fentanyl is shipped by Mexican traffickers using Chinese precursors. None of it comes from Venezuela.

Beyond that, Trump has reportedly been looking for a pretext to invade Venezuela since early in his first term. It would be “cool” to invade Venezuela, Trump told staff, according to John Bolton, his first national security advisor, because the country was “really part of the United States.”

Observers say Trump’s continuing fixation with Venezuela is firmly linked to the country’s oil wealth, with the world’s largest proven reserves. Already in 2018, Trump “wanted assurances regarding post-Maduro access to Venezuela’s oil resources,” Bolton wrote in his 2020 memoir, The Room Where It Happened. “Trump, as usual, was having trouble distinguishing responsible measures to protect legitimate American interests from what amounted to vast overreaching of the sort no other government, especially a democratic one, would even consider.”

Today, administration officials call his strategy a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, an 1823 declaration by President James Monroe saying European countries should stay out of the Western Hemisphere.

Personal History

I was in Panama during the U.S. invasion and, following Noriega’s capture and conviction, I conducted hours of jailhouse interviews with him for his memoir, America’s Prisoner. (I included my own independent assessments in the book and had no financial arrangement with Noriega.) I also tracked down the specific charges manufactured by his Panamanian opponents that led to his downfall. I concluded then, after interviewing U.S. military leaders of the era, that the invasion was, well, trumped up.

While Noriega may have taken money from traffickers, a senior Drug Enforcement Administration official told me at the time that Noriega had actually helped the DEA interdict drugs and protect U.S. agents. The drug case was so secondary to Bush’s actual political goals that prosecutors had to rewrite the original indictment against Noriega after the invasion just to ensure it would hold up. Similarly, today’s arguments against Maduro—certainly a dictator and rightfully under investigation by the International Criminal Court—are being bolstered by easily debunked claims like the cocaine canard. Still, Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, a recent Nobel Peace Prize laureate, has parroted the baseless claim that Maduro runs drug cartels threatening U.S. security.

Prior to the 1989 invasion, Noriega’s opponents manufactured a similarly convenient story: that the general had personally ordered the beheading of Panamanian dissident Hugo Spadafora and was plotting to flood the United States with cocaine. Neither charge proved to be true, nor had Noriega threatened to block the Panama Canal.

No matter. A combined U.S. force of 27,000 troops—including the 82nd Airborne Division, Army Rangers, and Navy SEALs—attacked Panama, a country the size of South Carolina. This, when only about a third of the 12,800 members of the Panamanian Defense Forces were combat-trained soldiers, and most were caught sleeping in their barracks. The assault also featured the first combat use of the Air Force’s F-117A Nighthawk jet fighters. The first-ever deployment of a stealth warplane was overkill, since Panama had no radar facilities nor operable air defenses. Organized resistance ended within 24 hours.

While the rhetoric is similar today, a U.S. attack on Venezuela would be a catastrophe on a completely different scale.

It would be “cool” to invade Venezuela, Trump told staff, according to John Bolton, because the country was “really part of the United States.”

Venezuela has a landmass twice the size of California and a population of 28 million—dwarfing tiny Panama’s 4.6 million. Its military includes more than 125,000 personnel, who could potentially be supplemented by 200,000 militia fighters. The military relies on aging Russian and Soviet-era aircraft and air defenses, much of it non-operational, but it receives training and strategic help from Cuba, Venezuela’s closest ally. Experts say its counterintelligence service, also trained by Cuba, is among the world’s best.

Post-Op Chaos?

Analysts say a post-invasion Venezuela would resemble not Panama, but the aftermath of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. U.S. troops easily swept to victory in Baghdad and other major cities, but the country’s political fabric was quickly ripped by the effective disbanding of the Iraqi military and the rise of Islamic insurgents. The U.S. occupation force was completely unprepared for the chaos and descent into civil war. Venezuela could well suffer similar factional fighting as cartel bosses, disenfranchised generals and leftist rebels compete for power.

There would be “chaos for a sustained period of time with no possibility of ending it,” Douglas Farah, a Latin America expert and president of IBI Consulting, told SpyTalk last month. Farah participated in war game exercises at the Pentagon during the first Trump administration that posited the outcomes of an overthrow of Maduro. The forecast was for disaster.

“The Trump administration does not appear to properly assess what the threat and strategic interests are,” Farah said. “The complexities of any of the available courses of action may elude them.”

Any significant attack would require firepower far exceeding the Panama operation. And unlike 1989, when the U.S. already had bases inside the country, an invasion of Venezuela would be a massive expeditionary lift.

Currently, at least nine Navy warships, including the supercarrier Gerald R. Ford, are on station in the Caribbean within striking distance of Venezuela. Maduro has reportedly responded by altering his own schedules and ramping up security. By some accounts, repression has been on the rise in Venezuela since Trump raised the ante.

But the real motivation for the president’s escalation resembles Bush’s prior to the Panama invasion: Trump, facing drooping poll numbers over “affordability,” violent immigration raids and the specter of expiring health insurance subsidies—not to mention his clumsy handling of the Epstein files—is flailing for a distraction from his woes. In this he looks remarkably like Bush in 1989 trying to shake the “wimp factor” and boost his approval ratings by attacking a foreign villain.

Dissension in the Ranks

Trump’s lack of a believable, much less a coherent, strategic predicate for his campaign against Venezuela is causing visible rifts between military and civilian authorities, just as it did in 1989.

Back then, Gen. Frederick F. Woerner Jr., the head of the U.S. Southern Command, resigned when he dissented over Bush’s plan to invade Panama. Woerner told me in an interview at the time that he had advocated leaving Noriega in power, and that he did not view the general as posing a danger to U.S. security. Woerner charged that the invasion plan was based solely on Bush’s political problems.

“Overall, I never saw any credible evidence of drug trafficking involving General Noriega,” Woerner said. “The invasion was a response to U.S. domestic considerations. It was the wimp factor.”

This week, history is rhyming. Adm. Alvin Holsey, the current head of the Southern Command, is retiring over disagreement with Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s campaign of extrajudicial attacks on small boats in the Caribbean. To date, there have been at least 22 such assaults, killing 87 people. While Trump and Hegseth describe the strikes as legitimate acts of interdiction, an array of critics and specialists in international law charge that they are illegal, potential war crimes, or even blatant homicides. The issue overheated after The Washington Post reported last month that Hegseth issued an order to “kill everybody” on a boat targeted on Sept. 2.

The tragedy is that, just like in Panama, a non-military solution may be possible—if the administration actually wanted one. Maduro has reportedly signaled a willingness to leave Venezuela as long as he and his family members had full legal amnesty, including from the International Criminal Court, and the removal of all U.S. economic sanctions. Trump rejected the deal. In the meantime, according to reports, wealthy Florida-based Venezuelan expatriates, in league with a pro-Trump former senior CIA officer, have been lobbying for Maduro’s removal. So too, of course, has been opposition leader Machado, who recently slipped out of Venezuela after months in hiding and headed to Oslo for the peace prize, which “re-established her as a major player in an escalating game of brinkmanship between President Trump and the Venezuelan leader, Nicolás Maduro,” according to the New York Times.

That seems a reach. But again, much of this mirrors the runup to the 1989 Panama invasion. Two months before the invasion, rebel members of the Panamanian military plotting a coup against Noriega begged Gen. Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, for support. Powell, consulting with then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, declined. Cheney later said that he and others were concerned the request for help could have been a setup by Noriega supporters. Donald Winters, who had served as CIA station chief in Panama, told me later that he could have persuaded Noriega to leave office freely in return for immunity and exile in Europe, but Bush administration officials blocked him from conducting the mission.

So Bush got his magnificent little war. Noriega was swiftly toppled. Twenty-three U.S. soldiers died, 325 were wounded, and hundreds of Panamanians—thousands, human rights groups said— were killed. Noriega was captured and remanded to the U.S. to stand trial. In 1992 he was convicted on eight of 10 charges of drug trafficking, racketeering, and money laundering and sentenced to 40 years in prison. He died in Panama in 2017.The invasion succeeded in its political aim—temporarily. A surge of support following the 1989 invasion gave Bush the popularity he sought, followed by another boost after U.S. and allied troops ousted Iraq from Kuwait in 1990-1991. But in the end, just two years later, it turned out that Americans cared more about the economy than they did about Noriega or Saddam Hussein. They sent Bush packing and elected Bill Clinton.

That could be Trump’s fate as well. But this time, the cost could be far higher.

Peter Eisner, a contributing editor to SpyTalk, reported from Venezuela, Panama, Mexico and throughout Latin America for The Associated Press and Newsday.

When I worked in the Casualty Care Research Center at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, we got reports on US activities, problem and were working to rename "friendly fire" as a problem. The best I saw was "Amicus Frater." And the conversation was about: "While there isn't one perfect Latin phrase, the closest concepts use Fratricidium (brother-killing) or Amicidium (friend-killing), from Latin frater (brother) + caedere (to kill) or amicus (friend) + caedere, describing the act of being killed by one's own side, a common term for "friendly fire". (Google)"

And as I remember, the major problem was with weapons that fired on their own or with little trigger action. From Bethesda it seemed to be a misguided mess.

You would have done well to interview Kurt Muse while writing this article.