Taliban Include Heroin Kingpins in Leadership

Obama and Trump scuttled a DEA-DoJ prosecution plan to spur peace talks with Taliban. Will Biden resurrect it?

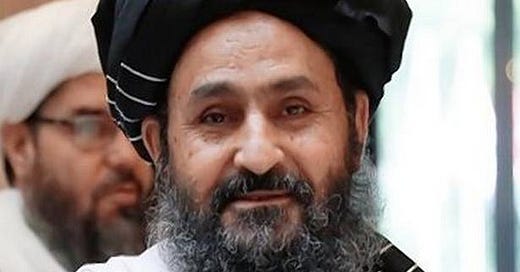

Nine years ago, a small team of Drug Enforcement Administration agents and Justice Department advisers formulated an ambitious strategy to use U.S. courts to prosecute 26 senior Taliban leaders and allied heroin traffickers under a criminal conspiracy. Multiple individuals identified as central to the conspiracy, including Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to SpyTalk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.