Senators Demand Answers from FBI on Failure to Disclose Evidence on Saudi Role in 9/11 Attacks

New York conference riveted by video of suspected Saudi agent ‘casing’ Washington, DC and new evidence of odd gaps in FBI and DoJ investigations

A pair of U.S. senators is demanding an accounting from the FBI about why damning evidence pointing to a likely Saudi role in the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks was hidden from key investigators and the public for more than two decades.

“Over the past year, crucial new evidence about the role of Saudi officials has been revealed publicly for the first time, even though it had been in the FBI since the weeks immediately after the 9/11 attacks,” Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut said Wednesday in a virtual address to a counter-terrorism conference organized in New York by the Soufan Center on the eve of today’s 24th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.pm

The mystery of why potentially explosive evidence had not been shared—including with the 9/11 Commission set up to investigate the attacks—has prompted Blumenthal and a Republican colleague, John Cornyn of Texas to write a letter to FBI Director Kash Patel demanding an accounting of the chain of custody on the bureau’s 9/11 material. The goal, he said Wednesday, “is to get to the bottom” of what happened to documents that—had they been shared in real time—could have been used to block a key suspect, a Saudi “student” who provided substantial assistance to two of the hijackers, from flying home to Riyadh rather than face American justice.

The momentum to reexamine the events surrounding 9/11 has picked up considerably in recent weeks in light of a federal judge’s ruling that gave a green light for a two decade-old lawsuit by families who lost loved ones in the attacks accusing the Saudi government of complicity in the attacks to proceed. Nearly 3,000 people died in the airliner attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and on a hijacked airliner thought to be headed to the White House or Capitol. Thousands more were injured.

Rejecting a motion by lawyers for Saudi Arabia to dismiss the case, U.S. Judge George Daniels ruled last month that there were “multiple pieces of circumstantial evidence” to draw the “reasonable inference” that two Saudis in the United States, Omar al-Bayoumi, the purported Saudi “student” who was being paid by a Saudi aviation company, and Fahad al-Thumairy, a radical imam at the Saudi-funded King Fahad Mosque in Los Angeles, were “coordinating with the Saudi government” when they provided considerable aid to two of the hijackers after they arrived in Southern California in January, 2000.

The ruling was stunning because, as John Miller, a former FBI and New York Police Department official who authored an early book on the 9/11 plot said at the conference, it threatens to “rewrite” what has long been the settled official story about whether there was any outside assistance in the Sept. 11 plot.

The 9/11 Commission had dismissed the idea of any Saudi role in the attacks, or that Bayoumi or Thumairy were implicated. But the Daniels ruling marks the first official analysis—from a federal judge, no less—that directly challenges that conclusion

What it means, at a practical level, is that lawyers for the families will at some point have new license to seek long buried documents about the 9/11 attacks from the FBI, the CIA and Justice Department that could shed light on the mysterious disappearance—and more recent reappearance—of evidence that potentially implicates Bayoumi and Thumairy as Saudi agents in arranging a full blown support network for the two 9/11 hijackers, Khaled Al-Mihdhar and Nawaf Al-Hazmi.

Questions about the chain of custody of evidence about Bayoumi in particular took on even more significance in recent days as a result of a Sunday Times of London report that a British Metropolitan Police officer who interrogated Bayoumi after the terror attack pleaded with U.S. authorities to seek his extradition to the United States, but that an unnamed Justice Department official—who, for reasons that remain unknown, apparently never saw the damning evidence of Bayoumi’s casing of the U.S. Capitol and other Washington landmarks, plus other evidence of complicity gathered by the British—rejected the idea, thereby allowing Bayoumi to return to Saudi Arabia.

Speaking for the first time, Detective Constable David Campbell, now retired, told the Times that he did “everything he could” to have Bayoumi extradited to the U.S., but was turned down.

“I still think about it, and I am shocked to this day,” Campbell told the Times.

Smoking Guns Gone

Most significant of all, Campbell said he was never given access to two potential smoking gun pieces of evidence that were seized by British police and then, before it could be fully examined, turned over to the FBI. That material, it now appears, was not closely analyzed at all, and never shared with others within the U.S. law enforcement and intelligence community, including with the 9/11 Commission. The handling of the case “stank to high heaven,” Campbell said. “I would have taken Bayoumi to the cleaners on those pieces of evidence.”

SpyTalk queried Philip Zelikow, executive director of the 9/11 Commission, about the new information by email Wednesday but did not get an immediate response. The FBI also declined SpyTalk’s request for comment.

Among the damning evidence shown Wednesday was the video of major Washington landmarks that Bayoumi prepared with two Saudi jihadis in 1999. It was shown at the same New York counter-terrorism conference where Blumenthal spoke by James Gavin Simpson, one of the main lawyers for the families, during a lengthy presentation that riveted the audience.

Watching the video on a large projector with Simpson’s narration proved much more powerful than the brief snippets that have been shown previously on television. The video shows Bayoumi lingering his camera on the entrances, exits and side gates of the U.S. Capitol. It shows images of security officials, with Bayoumi noting when they were leaving the building.

“This was not a tourist video,” said Simpson, rebutting the explanation by the Saudi lawyers. “This has all the hallmarks of an Al Qaeda casing of a terrorist target.”

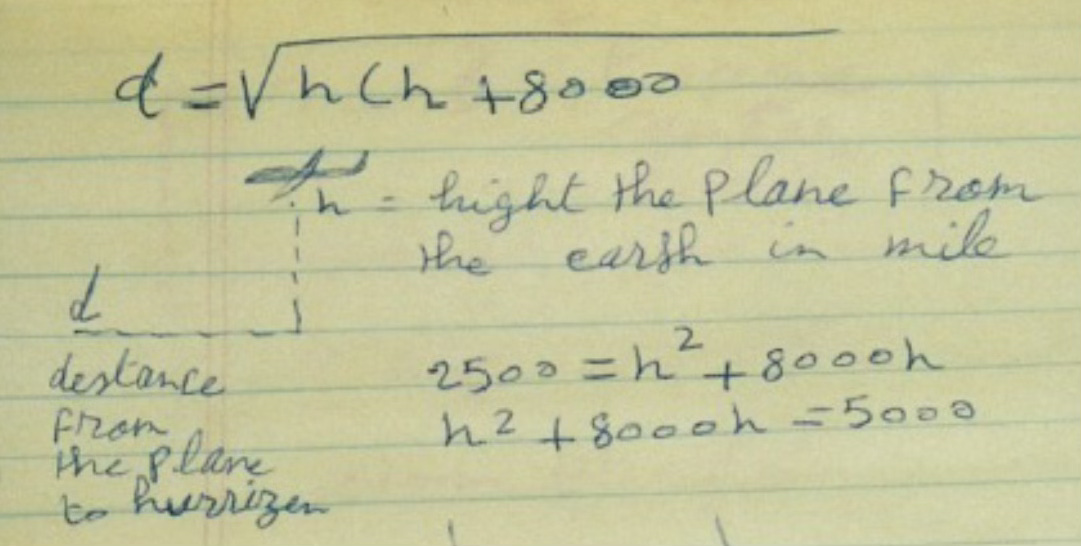

The video was initially seized by British cops at Bayoumi’s home immediately after the 9/11 attacks, along with jottings in a notebook that included a crude airplane sketch and an equation that purports to show how to calculate the downward descent of the plane. When he was questioned by lawyers for the 9/11 families in a deposition in Saudi Arabia, Bayoumi testified he couldn’t remember why he made the jottings, saying it was “an equation like any other equation.”

Odd Gaps

What makes this material important is that Bayoumi, from the beginning, was viewed as a potential suspect given his curious relationship with the two hijackers. As he explained to British police at the time and later in a deposition with the families’ lawyers, he just happened to have met al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi “by chance” at a Mediterranean restaurant in Los Angeles shortly after they arrived in the country.Then, seeking to help out fellow Muslims who spoke no English, he maintained, he invited them to join him in San Diego, where he found them an apartment, lent them money, set them up with a bank account and introduced them to other members of the Muslim community, one of whom was apparently Anwar al-Awlaqi, a notorious, U.S.-born Al Qaeda preacher who was later killed by an American drone strike in Yemen in 2011.

Bayoumi left the United States before the Sept. 11 attacks and was living in the United Kingdom when the hijacked airlines hit their targets in New York and Virginia. The 9/11 Commission, though, rejected the idea that Bayoumi was an Islamic radical who knowingly helped the hijackers to facilitate the 9/11 terror attack.

But Judge Daniels found that implausible, especially Bayoumi’s claim–endorsed by the Saudi government’s lawyers–that he was acting purely on his own. In the judge’s ruling, he noted that during a three month period between January 2000 and March of that year—key weeks when Bayoumi was helping the hijackers—FBI records showed there were multiple phone calls between him and Thumairy, the Los Angeles imam, as well as 93 calls between Bayoumi and the Saudi Embassy in Washington, 30 of which were to the embassy’s Islamic Affairs Department, many of whose officials had radical sympathies.

Detective Constable David Campbell, now retired, told the Times that he did “everything he could” to have Bayoumi extradited to the U.S., but was turned down. “I still think about it, and I am shocked to this day,” he said.

“Bayoumi was never acting alone,” said Simpson in his presentation. “He was, at every step, at every junction, coordinating with other officials in the Saudi government. He was, in fact, following instructions from the highest echelons of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s government when he assisted the hijackers.”

(Simpson, in a later interview, also shed some light on why the video and the airplane jottings seized by Birmingham police were not shared with British counterterrorism investigators when they had Bayoumi in custody–and why they were forced to let him go. The video, he said, was among 80 such videos that were seized by the cops – and then turned over to the FBI. But under British law, U.K. authorities could hold Bayoumi for only seven days unless criminal charges were filed. That was hardly enough time to analyze the contents of endless hours on the videos. It was only much later, when the FBI launched a follow-up investigation called Operation Encore, that Bayoumi’s video of the U.S. Capitol was discovered.)

In his presentation, Simpson also emphasized the families can draw a direct connection between Bayoumi’s entry into America and the Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation, a Saudi-funded entity that was accused by the U.S. Treasury Department and the United Nations of providing substantial aid to Al Qaeda. Simpson suggested the families have evidence that a former Saudi minister in charge of Islamic Affairs Departments and who then became a top official of the Al-Haramain Foundation dispatched Bayoumi to the United States in August, 1998, one week after the Al Qaeda bombing of two U.S. Embassies in Africa. The timing was significant, Simpson said, because Bayoumi’s mission was to begin preparations for the next attack, which unfurled on 9/11.

“It is our consistent submission,” Simpson said, wrapping up the families’ case, “that Saudi Arabia, through its Ministry of Islamic affairs, through its embassy in Washington D.C., through its consulates, notably in Los Angeles, and through its employees and agents and their subagents and proxies, conspired with Al Qaeda to provide the very forms of support that the hijackers needed to plan to prepare for and perpetuate the 9/11 attacks.”

Uncertain Path Forward

Just how and when Simpson will be able to actually present that case in court is far from clear. The Saudis have vowed to appeal, and one well-connected Saudi commentator told SpyTalk the Kingdom was not going to cave in to “ambulance-chasing lawyers.” But, if the Saudis do appeal, as expected, to the U.S. Court of Appeals in the Second Circuit—which they have until the end of next month to do—the next big battle won’t be over opening the actual evidence. It will be on the procedural issue of whether discovery should be stayed while the appeals process drags on, perhaps ultimately to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Which is another way of saying that finding out the truth about 9/11 is many more anniversaries away.

Isikoff should be arraigned on charges of criminal naïveté. Dubya's desperation to cover up the Saudi role in 9/11 was obvious from the beginning. He fairly begged Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah to visit him at his ranch in Crawford, Texas, which Abdullah finally did in April 2002, and made it clear throughout that a little thing like 9/11 would not be allowed to get in the way of a US-Saudi relationship served as the linchpin of American policy in the Persian Gulf. Indeed, the invasion of Iraq that followed 11 months later can be seen as little more than a gigantic effort to divert attention from the Saudi role since Cheney & Co. preferred to believe that Saddam Hussein was the real mastermind behind the attack. Isikoff's effort to reach out to Phil Zelikow, executive director of the 9/11 Commission, is especially laughable since Zelikow, who was in constant communication with the White House, saw to it that the commission would consistently downplay the Saudi connection. Why would Zelikow comment on a coverup that he helped create?