Mole Reversal

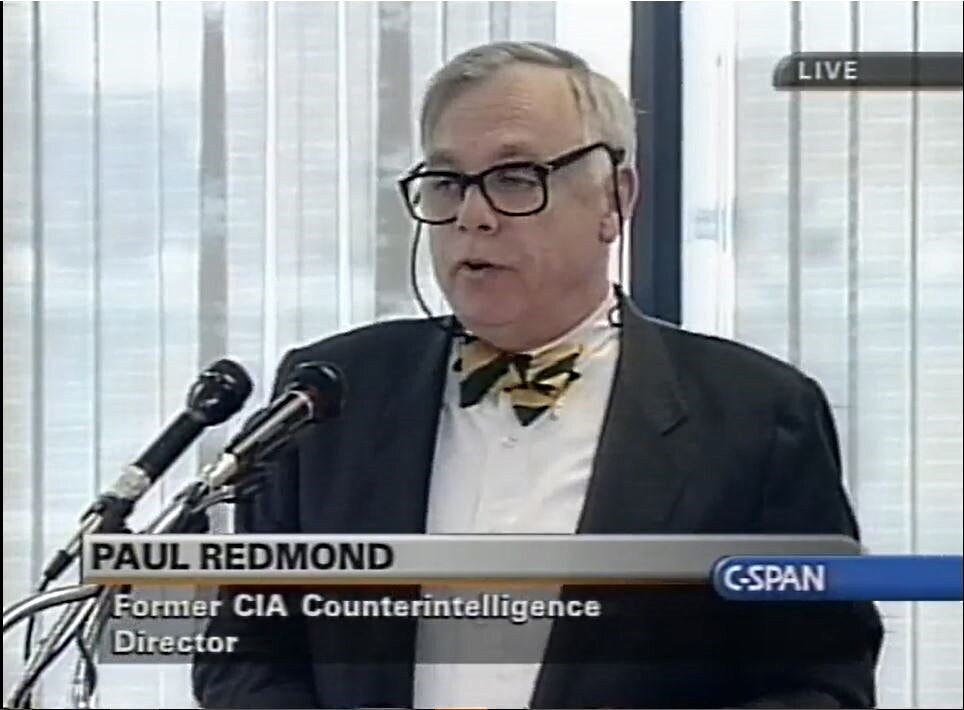

Former top CIA man Paul Redmond demands retraction of published accusation he was Russian spy

A top former CIA official has taken another step to beat back allegations in a recent book by another former CIA spy that he was a longtime mole for the Kremlin.

Paul Redmond, a legendary CIA counterintelligence official credited with jump-starting the infamous investigation that finally rooted out agency turncoat Aldrich Ames, was himself virtually accused of being a spy for Russia in a book published last summer by a fellow former CIA operative, Robert Baer.

Baer, who’s made a career as an author, filmmaker, opinion columnist and TV talking head since his resignation from the agency in 1997, maintains that the allegations against Redmond in his book, The Fourth Man: The Hunt for a KGB Spy at the Top of the CIA and the Rise of Putin's Russia, are not his but the conclusions of three CIA officers and an FBI agent assigned to a top secret internal mole-hunting team, the Special Investigative Unit. All are quoted extensively, on the record, in Baer’s book.

“I just reported the story as told to me by the [SIU] investigators,” Baer said in a brief interview Wednesday. True, to a point, but the former CIA man’s gripping narrative is tied closely to the recollections of the SIU members.

Redmond first counterattacked last November during a luncheon panel hosted by the CIA-friendly Association of Former Intelligence Officers at a hotel not far from the agency’s headquarters in Langley, Va. Flanked by fellow former senior CIA officials Lucinda Webb and Michael Sulick and other law enforcement officials, Redmond told a packed conference room that Baer’s book was fatally flawed by an uncritical reliance on faulty sources. Because the talk was off-the-record, reporters at the event were forbidden to write up the details.

But this week Redmond and his allies took a step out of the shadows. In another CIA-friendly forum, the daily Cipher Brief newsletter, they expanded on their arguments and urged the CIA to “prepare a comprehensive classified and unclassified analysis documenting the key inaccuracies in Mr. Baer’s book together with the historically correct facts”—and share it with the FBI.

If warranted by their review, they said, the CIA “and perhaps others in the Intelligence, Law Enforcement and policy communities should consider policy or legal remedies to provide access to records to correct slanderous allegations, when CIA policy and legal authorities do not prevent false accusations.” They also said the CIA’s publications review board should be more vigilant about sensitive material getting out. The PRB has been criticized plenty over the years for sitting on manuscripts and using the process to keep embarrassing revelations, not real secrets, from the public.

Fair Shot?

Redmond and company wrote that it was their “understanding” that Baer “did not offer Mr. Redmond an adequate opportunity to respond to the collection of false allegations prior to publication, nor give sufficient attention to key open-source information.” Baer denies that.

He said he talked to Redmond himself “a couple of times” while preparing his book. “He said, ‘No, I'm not a spy.’ It’s in the book.”

The “Fourth Man” title comes from the discovery of three previous Russian moles—Aldrich Ames, Edward Lee Howard (who escaped to Russia), and Robert Hanssen, a disgraced former high ranking FBI agent now serving 15 consecutive life terms in a supermax prison for exposing the identity of U.S. spies to the Russians. Perhaps two dozen, perhaps more, Russians were executed, because of their perfidy. Adherents of the “fourth man” theory say some of the losses in Russia can’t be explained by Ames, Howard and Hanssen alone.

Baer is hardly the first to raise the theory of one who escaped. Twenty years ago former senior CIA operations official Milton Bearden wrote that “American spy hunters continue to sift the ashes of espionage operations gone cold in the 1980s, searching for clues that might lead them to ‘the fourth man’—to what, it is hoped, will be the final traitor in a quartet of Americans who betrayed so many of our spies in Moscow during the Cold War.”

Former Soviet KGB officers have also said that at least one of its well placed spies got away.

Barr says he sent his pre-publication manuscript “to everybody involved” at the CIA and the FBI asking for their comments. In 2021, he said, two FBI agents visited him to discuss the case against Redmond. He got the impression their investigation was ongoing then and is continuing. “It's no longer the SIU's take,” he maintained. “It's the FBI's.”

Witch Hunt?

Redmond also personnally ridiculed Baer’s book this week in the International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, a forum for scholarly pieces on operations and history, enumerating a number of steps he took to shore up the agency’s Russia operations, not curtail them.

Redmond and his supporters said the views of Baer and his sources are “a troubling reminder” of a decades-long nightmare at CIA when its counterintelligence boss, James Jesus Angleton, saw Soviet agents everywhere in the agency and ruined many a career with his false accusations. The CIA director who finally fired him, William Colby, said Angleton’s delusions had just about paralyzed spy operations against the USSR.

Redmond, Webb and Sulick wrote that they want a “complete retraction and apology” from Baer.

That’s not likely.

“I stand by the book,” Baer told SpyTalk. “The three surviving members of the SIU told the same story, and reviewed the draft manuscript. “I’m not in a position to comment on whether or not they had full access to all relevant counterintelligence files. But their assumption is that they did.”

He added that, “all of my sources are willing to discuss this with the authors”—Redmond, Webb and Sulick—”should they be curious.”

UPDATE: Veteran national security journalist and author David Ignatius says he wishes “for both their sakes that this book had never been published.” See his thoughtful take here.

Baer deserves to be called to account for sloppy research on his part and, more so, for relying on the SIU for its findings on Paul Redmond. When I first heard of the SIU, I thought it probably had been formed to keep the three CIA members, all women, two of them known to me professionally, of the SIU busy, out of the hair of their seniors, including Redmond. The unit took itself seriously, however, and concluded that Redmond was a KGB spy, a conclusion with Angleton's stamp all over it. The CIA should have known that if it formed an investigative unit, it would get a result. Not one that would end up in a book, though.