Bungle in the Jungle

CIA schemes, Washington intrigue explored in riveting new US-Congo histories

First I have to tell you a story.

On a late autumn day in 1993, I went to see legendary former CIA station chief Larry Devlin at his apartment in Washington, D.C. It would be the first and last time we would meet.

Nothing if not gracious, Devlin greeted me at the door of his comfortable place, pointed toward the living room and then vanished, only to reappear with a pair of brimming martinis, never spilling a drop as he glided toward my chair across more than 40 feet of burnished parquet.

Then in his 70s, Devlin had long since retired from the agency after famously serving in Congo, where he befriended Colonel Joseph Desiré Mobutu, later known as the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. Mobutu played a crucial, behind the scenes role after independence in 1960, as the key figure in a coup that led to his appointment as Army Chief of Staff. Mobutu would often break bread at Devlin’s house in the capital, where the duo would go over impending cabinet selections, or foreign policy or how the country needed to cast particular votes in line with U.S. policy at the United Nations. Mobutu later seized full presidential powers in 1965, holding sway over his mineral-rich country — the size of America east of the Mississippi — for more than 30 years.

After a perfunctory toast, the genial Devlin began to interrogate me in a low voice about my own recent encounters with Mobutu—when the supremo received me, then a correspondent for Time magazine, over several days in one of the elaborate palaces dominating his ancestral village, set amid vast jungles just beneath the equator.

Devlin’s reddish, watery eyes glinted through thick glasses (perhaps, I thought, with emotion), when I let him know that Mobutu had asked me to pass along his warm regards.

Devlin, arriving in Congo only days after it gained independence in June 1960, witnessed a violent struggle for power as he maneuvered to curtail the role of Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first prime minister, a charismatic and mercurial figure considered by some, especially the U.S. State Department and the CIA, as a likely Soviet tool.

To that end, Devlin may have done Mobutu the ultimate favor when he warned him of an impending assassination attempt. But when it came to Lumumba, although Devlin quietly refused to carry out CIA assassination plans, he later encouraged the by-then ousted premier’s transfer into the hands of political enemies who predictably murdered him. Mobutu, apparently keeping friends close and enemies closer, had been an early and trusted military aide to Lumumba, before covertly facilitating the plot that would end his life.

After Mobutu was more firmly entrenched in power, the CIA brought Devlin back to Washington. But before he left, Le Guide, as the dictator was known, drove over to Devlin’s house in a convertible white Chevy Impala with a large photograph of himself bearing the words, “To my old and excellent friend L. Devlin, to whom the Congo and its chief owe so much.”

Utility Player

Back home, the CIA soon sent Devlin off to run the so-called secret war in Laos against North Vietnamese-allied guerrillas, the agency’s largest covert action at the time. Devlin later skippered Langley’s Africa Division and retired in 1974, heading back in 1976 to Congo—by this time renamed Zaire—as the personal hire of Maurice Tempelsman, a major Democratic party donor whose diamond companies did business in Congo. In 1977, Tempelsman’s longtime legal consigliere, JFK aide Theodore Sorenson, was nominated to be CIA director (although the nomination failed).

Balancing a martini glass in one hand with a pen in the other, I managed to wrest back control of my interview from Devlin (or so I thought), and tried to guide him through a discussion of his role in Mobutu’s rise to power. How did Le Guide slip his CIA leash (never that tight) and morph into a king-sized kleptocrat prone to using force against his own subjects? (At the insistence of Devlin, who died at 86 in 2008, our interview was on background only.)

At one point, I asked Devlin whether his backing of Mobutu and decades of subsequent CIA support had been worth the price—as measured in official corruption, torture and the deaths of several million people, many of them in conflicts that Mobutu initiated, abetted, or was unable to prevent, despite his posture as a great national unifier.

At another point, I tried to prod Devlin with excerpts from my interviews with Mobutu’s longtime former personal physician, Bill Close (the now deceased father of actress Glenn Close). During his 16 years tending to Mobutu’s mild hypochondria (and fighting disease around Congo), Close said he and the dictator would relax as friends over glasses of cognac or a favorite pink champagne flown in from France. Among other things, Close told me how Mobutu regaled him with funny stories about the senior State Department officials sent to complain of his atrocious human rights record and theft of U.S. financial and military aid. Close recalled how a chortling Mobutu performed surprisingly spot-on voice imitations of Foggy Bottom pooh-bahs telling him to clean up his act or risk losing American support. According to Close, such American “threats” were repeated, year after year.

Poised, never defensive or even apparently ruffled, Devlin simply ignored many of my questions. Instead, he calmly delivered a shorter version of the testimony he had given to the 1970s Church Committee probe of the CIA — when he appeared using his cover name, Victor S. Hedgman. Devlin later elaborated on and recycled that testimony in his subsequent ghost-written memoir, Station Chief, Congo: Fighting the Cold War in a Hot Zone, published in 2008.

As Devlin riffled through his version of the past, I found myself warming to the man, and his more than occasional flashes of dry humor. At the same time, I wondered if, just maybe, parts of his narrative might amount to the well-rehearsed performance of a professional prevaricator (for in the spy business, as in Churchill’s observation about war, the precious truth is attended by a bodyguard of lies). And I could never get Devlin off message, not to mention his robotically circular argument that there was absolutely no alternative to the Cold War imperatives with which he justified nearly all that he and the agency had done in Congo.

As Devlin modestly suggested, he had merely given a hand up to a proud African leader who was in close contact with the agency ever after. Le Guide went on to suppress attempted communist mischief-making in his own country, even as Congo, later Zaire, routinely voted in support of key U.S. Cold War policies at the United Nations. Mobutu also allowed the CIA a platform to support important clandestine operations in neighboring Angola and other countries.

As our beverages drained away, I managed to reflect that Devlin was in effect serving me from the same rhetorical cocktail shaker long used to soothe or sink well-meaning critics of other CIA clients: the Shah of Iran and authoritarians in various parts of the world. Of course a host of progressives would have preferred different U.S. policies, notably in Congo. Yet Devlin’s scheming there was considered a significant success by CIA Director Allen Dulles and the few others in Washington who may have known, notably Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy—content that their fears of a communist threat had been kept at bay.

Since my long ago visit with Devlin, a variety of declassified documents have emerged, including records of the U.S. Senate’s Church Committee, and other secret materials the panel never saw. In 2010, former House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee chief of staff Steven R. Weissman wrote an important 2010 article in the journal Intelligence and National Security, in which he assembled and analyzed much of the new material, giving a more complete and accurate picture of what had actually happened in Congo during Devlin’s tenure—and, to put it kindly, the lack of candor and sins of omission that suddenly jumped out in Devlin’s testimony to Congress and subsequent pronouncements. This past summer Weissman also published a memoir that added more flesh to the story— more about which anon.

But first I want to talk about another new and important work on Congo in the volatile 1960s and onward, The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination, by Stuart A. Reid. An executive editor of Foreign Affairs, Reid offers a richly-detailed and deeply sourced narrative beginning with the early life of Lumumba, a one-time postal clerk, beer salesman and so-called evolué, a reference to the few Africans whose education and facility in French might allow them to hold positions of responsibility. At Congo’s independence in 1960, after 75 years of grotesque Belgian mis-rule, the ranks of evolué were minuscule, and only 30 native Congolese had any kind of university degree. It was in this context that the politically-gifted if inexperienced Lumumba managed to win power at the ballot box.

His victory upset not just Congolese political opponents, but the U.S. and one-time Belgian colonials hoping to maintain their privileged status in a country they no longer ruled. In one memorable example of Lumumba’s penchant for speaking truth to power, he stunned the audience at a speech by King Baudouin marking the end of Belgian control in Congo. No sooner had the tone-deaf monarch finished praising the “genius of King Leopold II,” the king’s forebear and rapacious founder of the Congo Free State, than Lumumba delivered his own address excoriating Belgian atrocities.

“We have seen our lands spoiled in the name of laws which only recognized the right of the strongest,” Lumumba told assembled dignitaries, condemning the “insults and blows which we had to undergo morning, noon and night because we were negroes.”

The king was not amused. Neither were the many ex-colonials in attendance.

Within days of Lumumba taking office, a mutiny by indigenous troops against their Belgian officers prompted resident whites to fear for their lives. Lumumba also faced a breakaway insurgency in Katanga province, location of most of the country’s mineral wealth. When he failed to get the support he wanted from the U.S.— or Belgium, which was greedily backing Katangan independence—the non-ideological, increasingly desperate Lumumba suggested he would seek Soviet assistance. He managed to persuade United Nations Secretary General DagHammarskjöld to bring in more than 10,000 peacekeeping troops to stabilize the situation. But by this time the U.S. was deeply alarmed by what it saw as the premier’s potential to become an African Castro. With coaching from Devlin and Belgian connivance, Mobutu then ousted Lumumba in a military coup.

All told, the doomed prime minister served in office for only ten weeks before his overthrow and confinement. As a prisoner, he was eventually transferred to Katanga (once again with Devlin’s knowledge and support, according to records) where he was severely beaten by the province’s top leader at the time, Moïse Tshombe and others and, on Jan. 17, 1961, shot to death.

Devlin later acknowledged being supplied with a syringe for injecting poison into a tube of toothpaste that could be used to assassinate Lumumba. The Agency’s top technical wizard, using the pseudonym “Joe from Paris,” flew in personally from Washington to deliver the dentifrice and other goodies. Around the same time, Devlin asked the agency to quickly send him a “high-powered foreign-make rifle with telescopic scope and silencer.” Glibly, he added, “The hunting is good here when the light’s right.”

Reid points to declassified U.S. official records that confirm the veracity of Devlin’s repeated, though limited denials to the Church Committee (and later) of any U.S. role in physically ending Lumumba’s life. But records also show what Devlin failed to mention: that, three days in advance, he had been alerted to plans that would predictably lead to Lumumba’s death. In doing nothing to stop the killing and actively encouraging Lumumba’s transfer into the hands of his political enemies, Devlin helped accomplish the CIA’s goal of terminating the ousted premier without directly implicating the agency.

As Reid writes, “Larry Devlin had a hand in nearly every major development leading up to Lumumba’s murder, from his fall from power to his forceful transfer into rebel-held territory on the day of his death.”

Dental Trophy

One of Lumumba’s only surviving body parts was a single gold-crowned molar, salvaged as a trophy by a Belgian policeman before the murdered leader’s corpse was chopped into pieces and dissolved in sulphuric acid. The gilded fragment was first taken back to Belgium by the policeman, who apparently kept it for 20 years in a padded box in his home, before displaying the object on television and boasting that he had also absconded with another Lumumba tooth and part of one of his fingers.

As Reid unspools the story, the policeman’s TV appearance eventually triggered the 2022 repatriation to Congo of the Lumumba tooth shown on TV, where it toured the country and was enshrined in a mausoleum with full military honors in a ceremony attended by the country’s top leaders and Lumumba’s surviving children.

Reid argues that Lumumba’s removal had broad consequences. As he writes, “the episode marked a turning point, the definitive end of a short-lived democratic experiment, and the beginning of decades of poverty, dictatorship and conflict.”

The crisis also stands out as a significant milestone in the Cold War, theretofore largely confined to Europe. But after the CIA’s “success” in central Africa, the U.S. embarked on a series of attempts at regime change at least as damaging including assassinations, everywhere from the Bay of Pigs, to Vietnam, Nicaragua and, eventually, Iraq and Afghanistan.

United Nations peacekeeping forces also faced their first major test in Congo. The chaos following Lumumba’s assassination quickly emerged as a backdrop to the demise of U.N. Secretary General Hammarskjöld, who died in a mysterious plane crash as he shuttled around trying to calm the situation. Meanwhile, the spirit of Lumumba lived on as an avatar of the struggle against colonial and neocolonial rule across Africa and in the Global South.

Jawaharial Nehru, a nationalist leader and India’s first prime minister—who provided thousands of troops to the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Congo— called Lumumba’s murder, “an international crime of the first order.”

Yet Lumumba’s demise was quietly celebrated in Washington. Devlin later explained his resistance to carrying out the murder himself on moral and political grounds, calling the idea dangerous, because U.S. involvement might be discovered, creating a backlash against American policy and threatening American lives.

The most likely explanation, cited by Reid and others, appears to be that the agency was in hyper-cautious mode before and around the time of Lumumba’s murder—as it prepared for the newly-elected President John F. Kennedy to assume power. Agency leaders naively expected that the Democrat might favor a less aggressive approach to assassinations and foreign spy ops. But Reid says that soon after taking office, the administration okayed more of Devlin's bribes for Mobutu and his loyal troops, and approved a scheme to buy off members of the Congolese parliament so they would politically neutralize the murdered Lumumba’s remaining supporters. A declassified document reveals that Devlin cabled the agency that it “could take major credit for the fall of the Lumumba government and the success of the Mobutu coup,” hailing its role in choosing a successful nominee as Lumumba’s successor in office. By 1963, Mobutu was flying to Washington for a Rose Garden photo-op with JFK and lunch in Langley.

Months earlier, before Kennedy won in November 1960, Devlin avoided overtly opposing agency schemes to kill Lumumba—for fear, he said, of finding himself replaced by a more compliant station chief. So he quietly played for time. Then, after the election, when he learned Lumumba would soon be transferred into what amounted to a death zone, he encouraged the plan, but did not inform his CIA bosses for three days, until the murder was a fait-accompli—in case their politically-induced caution led to unwanted interference.

Masterful Case

At more than 600 pages, including copious footnotes, Reid has assembled a cogent description of a menacing shift in Cold War history, encompassing the end of colonial rule in one of Africa’s most strategic countries, and the start of a new era fraught with uncertainty and foreign interference that has only continued. With telling detail, story-telling élan and descriptions drawn from four visits to Congo, he includes a wide array of interviews, the recollections of observers and participants in the drama, living and dead, records from congressional hearings and de-classified documents.

Some critics have argued for less blame on the CIA, and more on Belgium’s horrific colonial rule and feckless lack of preparation for Congo’s independence. Yet the sheer abundance of Reid’s research demonstrates that, while there’s plenty of fault to go around, the role of Devlin and the CIA was crucial. It also shows that the report on the CIA in Congo by the Church Committee, and near exoneration of Devlin and the agency, was not the whole story. And it comes with a pot boiler’s plot-line and judicious marshaling of facts that do not slight Belgium’s malign role. Highly recommended reading — and not just for Congo, spy and history buffs.

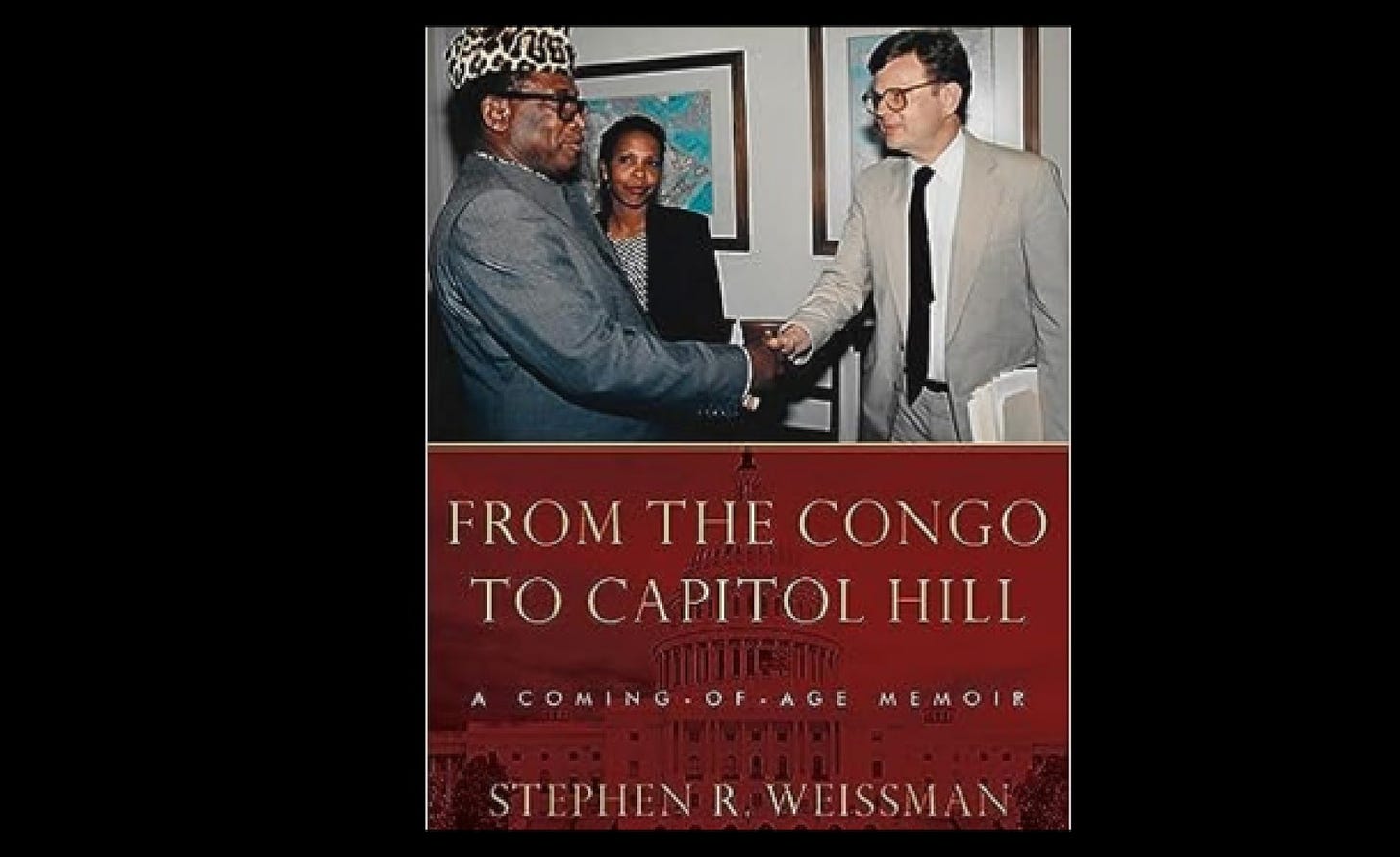

But back to Steven Weissman, and his very personal retrospective, From the Congo to Capitol Hill: A Coming-of-Age Memoir. With knowledge he first acquired as a young academic teaching in the country (1969-1971) and, later, as an influential advisor to the House Subcommittee on Africa (1979-1991), Weissman is a deeply experienced Congo- watcher.

Much of the detail set forth in his earlier Intelligence and National Security article , goes unmentioned in this volume. Instead, Weissman offers some 220 pages of highly personal story-telling, beginning with how, with a recent PhD in political science, he, his wife and infant child lived in Kisangani (the former Stanleyville) where he taught at a local university.

Weissman has a good eye for scene-setting. The highlight of the first part of his story comes when student protests erupt at his university. Though not directly related to Congo’s governance under Mobutu, ever-vigilant university administrators and local security elements perceived a potentially more serious threat and cracked down. Weissman, an admitted liberal and occasional advisor to some students, was unexpectedly accused of complicity in the events, eventually leading to his forced departure from the country.

Weissman concedes his own naiveté, and admits that some of his apparently innocuous actions on behalf of students allowed local authorities to seize upon and misconstrue his conduct. In his telling, as the student demonstrations became more politically sensitive, even his appeal for help to the U.S. embassy in Kinshasa fell on the deliberately deaf ears of officials who just didn’t want to risk upsetting the host government. A good deal more surprising was how, years later, the mostly trivial incident popped up again as Weissman was serving as a key advisor to two successive House subcommittee chairmen, both critics of Mobutu, and U.S. assistance to his ever-more corrupt regime. At this point, Mobutu himself, and various Republican members of Congress (in some cases, Weissman says, recipients of campaign contributions from pro-Mobutu Washington lobbyists) managed to resurrect Weissman’s long ago alleged transgression, targeting him with personal attacks and blame for the controversy over U.S. aid to Congo.

These and other colorful tales make up the instructive, if disconcerting second part of Weissman’s book, an insider’s look at the political maneuvering and sausage-making that can accompany congressional aid supposedly designed to benefit foreign lands—not just prop up an American-backed dictator, or U.S. vendors doing business in the country. Weissman offers a well-informed perspective based on decades of experience, enlivened with strong narrative, telling anecdotes and detail.

Given the moral and political complexity that lies at the heart of both Reid’s and Weissman’s histories, it’s noteworthy that their relevance extends well beyond Lumumba, Devlin, Mobutu and even Congo itself.

The events and arguments date from earlier eras, but many of the same challenges remain with us. That’s why scholarship that sharply questions the public record offers not just a good read, but a timely and cautionary tale. As the spook master says in John Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, “You can't be less wicked than your enemies simply because your government's policy is benevolent.” Devlin might have agreed with that proposition, but today’s readers may be less inclined to do so.

Adam Zagorin is a former senior correspondent for Time magazine. Read his 1993 interview of Mobutu in his Gbadolite palace here.

A good read, and an important reminder that much continues to happen in Africa and the Global South while most of us are focused on Gaza, Ukraine, and China. Learned a lot.

More than half a century ago, a friend of mine, who was in the Congo with our government, but not the CIA, at the time of Lumumba's death, told me much the same story about the death itself. This doesn't alter the CIA's complicity in the affair or the wide-spread belief that the CIA pulled the trigger. The Soviets were quick to exploit the situation in their propaganda, of course.