A War Story Fit for Christmas

'Midnight Flyboys' is a riveting tribute to the pilots who ferried secret agents into Nazi-occupied Europe

GENERATIONS OF US have now grown up reading or watching stories about the courage and heroism of the “Greatest Generation,” those young men and women who risked their lives in the existential battle against fascism in World War II. Yet, even 80 years after the guns fell silent, new chapters of that vast conflict continue to emerge, reminding us that the war was fought not just on the beaches of Normandy or the islands of the Pacific, but in the shadows.

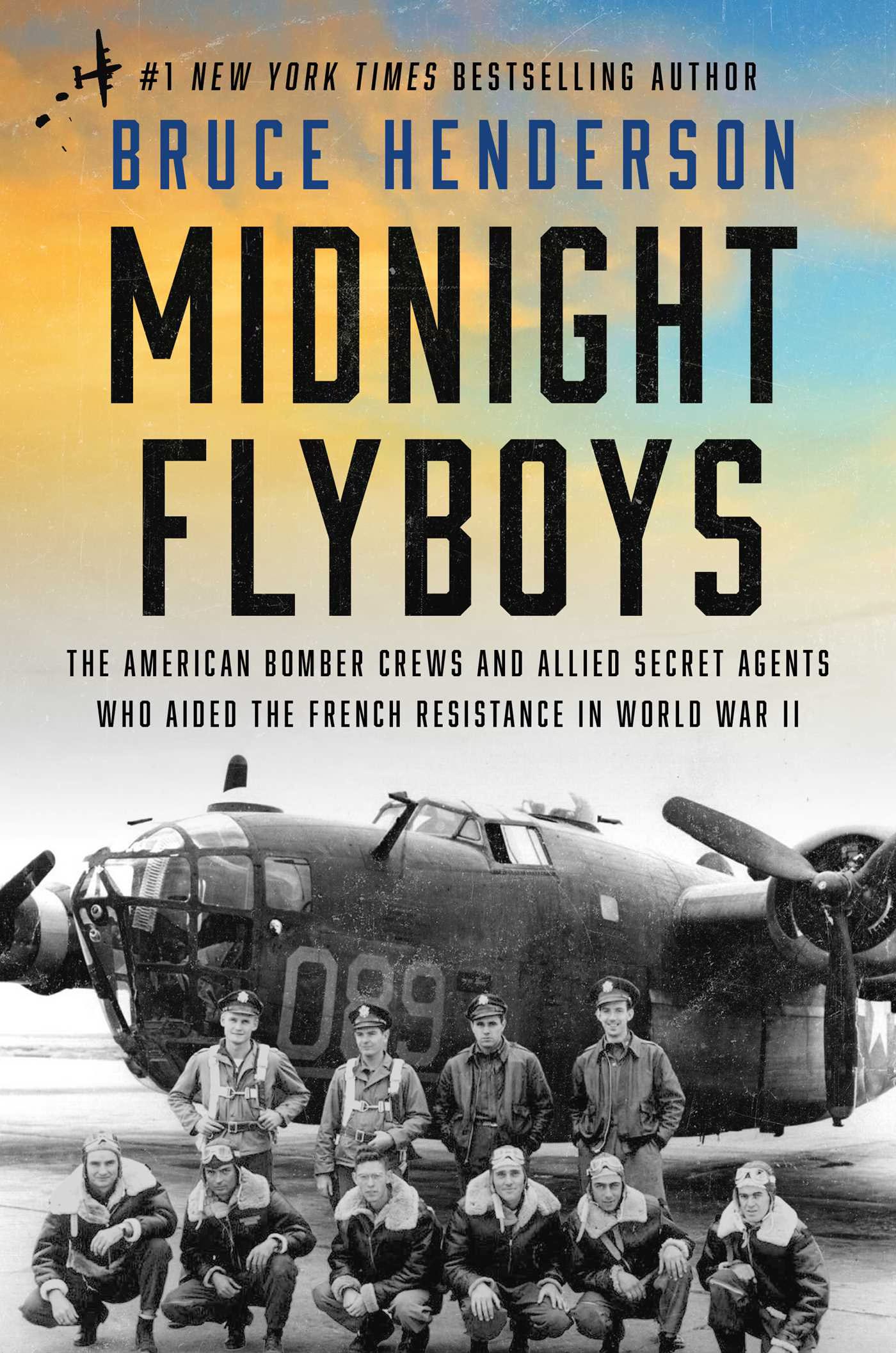

Bruce Henderson’s captivating new book, Midnight Flyboys, takes us back to those days of danger and glory, illuminating a specific, harrowing campaign that has long remained a footnote in the broader history of the air war. It centers on the operations of the code-named “carpetbaggers”—U.S. Army Air Force pilots who flew modified B-24 bombers on low-altitude, nighttime missions to drop supplies and allied agents behind enemy lines. Central to this story are not just the aviators, but the intrepid spies—many of them women, by the way—who volunteered to hitch rides on these treetop missions, parachuting into the peril of Nazi-occupied Europe.

Henderson is no stranger to these themes; he has written frequently, and always engagingly, about the human element in war. His previous book, Sons and Soldiers, chronicled the German-Jewish emigres who escaped Europe only to return as U.S. soldiers. The “Ritchie Boys,” as they were called, after the name of the Maryland camp where they trained, interrogated German POWs and provided key intelligence that aided the allied victory. In Midnight Flyboys, Henderson turns his gaze from the interrogation rooms to the cockpits and the drop zones, focusing on a moment when the air war over Europe shifted into high gear.

It is inspiring, and sobering, to read these accounts of such selfless warriors today. Most of the fighters were barely old enough to vote. My father was a 22-year-old Navy officer when he was assigned to a ship in the South Pacific. My friend, the late Col. Robert Z. Grimes was just 21 when he began piloting B-17 bombers over Nazi territory.

Kurt Vonnegut, himself a veteran and POW in a Nazi prison camp, captured this reality perfectly in Slaughterhouse-Five, which he struggled to write for 20-plus years after the war ended. When Mary O’Hare, the wife of one of his army buddies, accused him of planning to write a book that would glorify war, she said: “You’ll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne.” Vonnegut promised her he would tell the truth. “I’ll call it ‘The Children’s Crusade,’” he told her, and included it as a subtitle. By then, it had taken Vonnegut multiple drafts and 5,000 discarded pages before he could finish the story of his imprisonment in Dresden during the 1945 allied firebombing that killed 25,000 “Hansels and Gretels,” as he put it.

Overnight Adults

Midnight Flyboys is, in essence, a chronicle of another children’s crusade—one fought in the dark, by “boys” flying heavy machinery and “girls” jumping into the void.

By late 1943, the allied command had authorized a new, top-secret mission. For months, the Eighth Air Force had been pounding Nazi installations in dangerous daylight raids, flying in massive formations at 25,000 feet. But the resistance movements in France and the Low Countries needed more than bombs; they needed guns, radios, money, and leaders. Operation Carpetbagger was born as a joint enterprise between Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and its American counterpart, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). To execute the plan, they needed a plane that could carry a heavy load—a bomber

They chose the B-24 Liberator. While the B-17 Flying Fortress had been the beloved workhorse of the daylight campaign—famed for its ability to take punishment and bring crews home—the B-24 was faster and had a longer range. However, it was also physically demanding to fly—like flying a truck, the pilots said. For the Carpetbaggers, these planes were stripped of their belly turrets and nose guns to save weight and painted black to evade searchlights. They became the hot-rods of the heavy bomber world, designed not to fight, but to run.

Henderson describes an early recruiting session that sets the tone for the book. “You’ll learn to fly four hundred feet above the ground at ten miles per hour over stalling speed,” Col. Robert W. Fish, the operations officer, told the assembled pilots. The mission profile was terrifying: fly alone, at night, without fighter escorts, navigating by landmarks and moonlight to find a specific field in France where a resistance fighter might be waving a flashlight. Henderson writes that “one mistake, and the aircraft could suddenly dive and the pilot might not be able to regain control before colliding with the ground.”

Fish gave the men a few minutes to leave if they wanted to. One pilot recalled being “dumbfounded” by the virtual suicide mission being proposed. Yet, in a testament to the spirit of the time, none of them backed away. By early 1944, the Carpetbaggers were flying hundreds of sorties. Their bomb bays were stripped of bomb payloads and retrofitted with canisters of bazookas, rifles, bicycles, and medical supplies. And through the “Joe Hole”—the opening in the floor where the ball turret used to be—they dropped the agents along with the supplies.

Henderson brings this history to life through the personal stories of the crews and the spies, the “Joes” and “Josephines.” It is here that the book sparkles, though it occasionally stumbles into stylistic traps, such as relying on casting-call descriptions that border on caricature. The airmen are “big-boned,” “cigar-chomping,” “man’s men.” The women show up as “petite,” “spirited,” or “dark-eyed beauties.”

For a one time only half-off Christmas holiday subscription, click here. Offer ends on December 31.

These descriptors feel unnecessary. The actions of these women were bold and brave enough that they do not need to be softened or romanticized. They were warriors, full stop. Take Nancy Wake, one of Henderson’s central personalities. A New Zealand-born woman with wanderlust, Wake was far more than a “hazel-eyed brunette with a sparkling smile.” She was a force of nature who graduated from challenging the Nazis with her pen to killing them in combat.

Henderson recounts her backstory with relish. After living in Vancouver and New York, she bluffed her way into a job with the Hearst Newspapers by claiming to speak “Egyptian.” “I love Egypt! I’ve been there many times!” she told her interviewer. She had never been there, nor, of course, is “Egyptian” a language -- it’s an Arabic dialect. But that brazen confidence served her well. Based in Paris in the 1930s, she witnessed the rise of Nazism firsthand. When the war broke out, she didn’t flee; she joined one of the escape lines in occupied Europe, teams of underground operatives who sheltered downed allied airmen and helped them cross the Pyrenees into Spain.

Eventually recruited by Britain’s SOE, Wake found herself in a B-24, staring down through the Joe Hole at the dark French countryside below. The jumpmaster told her, “If you’re afraid, ma’am, we’ll take you back.” Wake’s response was legendary: “I want to get out of this bloody plane!”

She did need a shove to get out of the plane, but once on the ground she became one of the most effective resistance leaders of the war, organizing thousands of French resistance fighters and leading raids against German garrisons.

Brave Beyond Belief

Stories like Wake’s remind me of the interviews I conducted for my own book about the underground and escapees, The Freedom Line. I often wonder if the pilots I wrote about—those who were shot down and smuggled out by the so-called Comet Line—ever crossed paths with the Carpetbaggers. The world of the resistance was a web of tenuous connections, held together by moxie.

While Henderson’s narrative is gripping, the book is not without flaws beyond the gendered stereotypes, Henderson employs a technique common in popular history but sometimes irritating: the scattering of foreign language phrases into dialogue to establish a cinematic atmosphere.

In one passage, an SOE officer describes the dangerous work to a recruit. “En France?” the recruit asks. “Oui, en France,” the officer replies. We know they are speaking French; we know they are in Europe. The dialogue feels staged, an unnecessary flourish.

However, these are minor nits in a terrific account. Henderson excels at explaining the technical challenges of the missions—the “dead reckoning” navigation, the reliance on early radar sets, and the sheer physical exhaustion of wrestling a four-engine bomber at treetop level. He captures the claustrophobia of the aircraft and the bone-chilling cold of the unpressurized cabins.

He also touches on the moral clarity that drove these young people. About 25 years ago I interviewed Grimes,the former B-17 pilot, for The Freedom Line, and like the pilots in Henderson’s book, he was unconvincing when he downplayed his bravery. “I was too young and too dumb to know any better,” he told me. But reading Midnight Flyboys, one realizes it wasn’t just youth or ignorance that dulled their answers, it was a sense of purpose. Whether they were “cigar-chomping” pilots or “petite” spies, they shared a conviction that the world was broken and that it was their job to fix it.

The “Joes and Josephines” were not super-soldiers. Only months earlier they had been civilians—journalists, teachers, mechanics—who learned how to kill and to survive. They often carried cyanide pills in case of capture. They knew the Gestapo torture chambers awaited them if they failed. Yet they jumped.

These days, so few World War II veterans are left to look back at those nights. We depend on archives, memoirs, and historians like Henderson to assemble their stories before they entirely fade away. Midnight Flyboys serves as a vital act of preservation. It reminds us that the liberation of Europe was not just a result of massive armies clashing in daylight, but of lonely, terrifying flights across the Channel in the dark, delivering the tools of freedom to those waiting in the shadows.

Just below the surface of our society, in red states and blue states alike, we find men and women whose parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles fought this fight. They were part of a “Children’s Crusade” that actually succeeded. As we face new threats of authoritarianism and global instability, stories like these are not just nostalgia; they are a challenge. They ask us if we, too, would have the courage to jump into the dark. ###

SpyTalk Contributing Editor Peter Eisner is an award-winning reporter and editor, formerly at The Washington Post, Newsday, and the Associated Press. He is the author of a nonfiction trilogy about World War II: The Freedom Line, The Pope’s Last Crusade, and MacArthur’s Spies.

Why have there never been any films made or a "Band of Brothers" kind of TV series made telling the stories of these heroes and heroines? Sounds like a treasure trove of material!