A Seat in a Spy Swap Drama

Michael Isikoff recalls his small part in a big U.S.-Cuba Cold War drama told in a new podcast series, "I Spy: The U,S,, Cuba and the Secret Deal that Ended the Cold War."

One February evening 10 years ago, I strolled through the streets of Havana with the so-called Cuban 5— a band of Communist spies whose ringleader, Gerardo Hernández, had just been released from a U.S. prison in California. It was a wild and wholly improbable scene. Barely six weeks earlier, Hernández had been serving a double life sentence for conspiracy to commit espionage and murder, with no possibility of parole. HIs fate seemed doomed.

But then, thanks to a stunning agreement between President Barack Obama and Cuban leader Raul Castro to restore diplomatic relations after more than 50 years of Cold War hostilities, Hernández was a free man, the result of super secret negotiations that produced a classic spy swap: Hernández and two of his Cuban 5 colleagues still in U.S. jails were let go in exchange for Cuba’s release of a CIA mole who had penetrated Havana’s intelligence directorate, and an American contractor, Alan Gross, who had been locked up for years by the Cubans on suspicions of espionage.

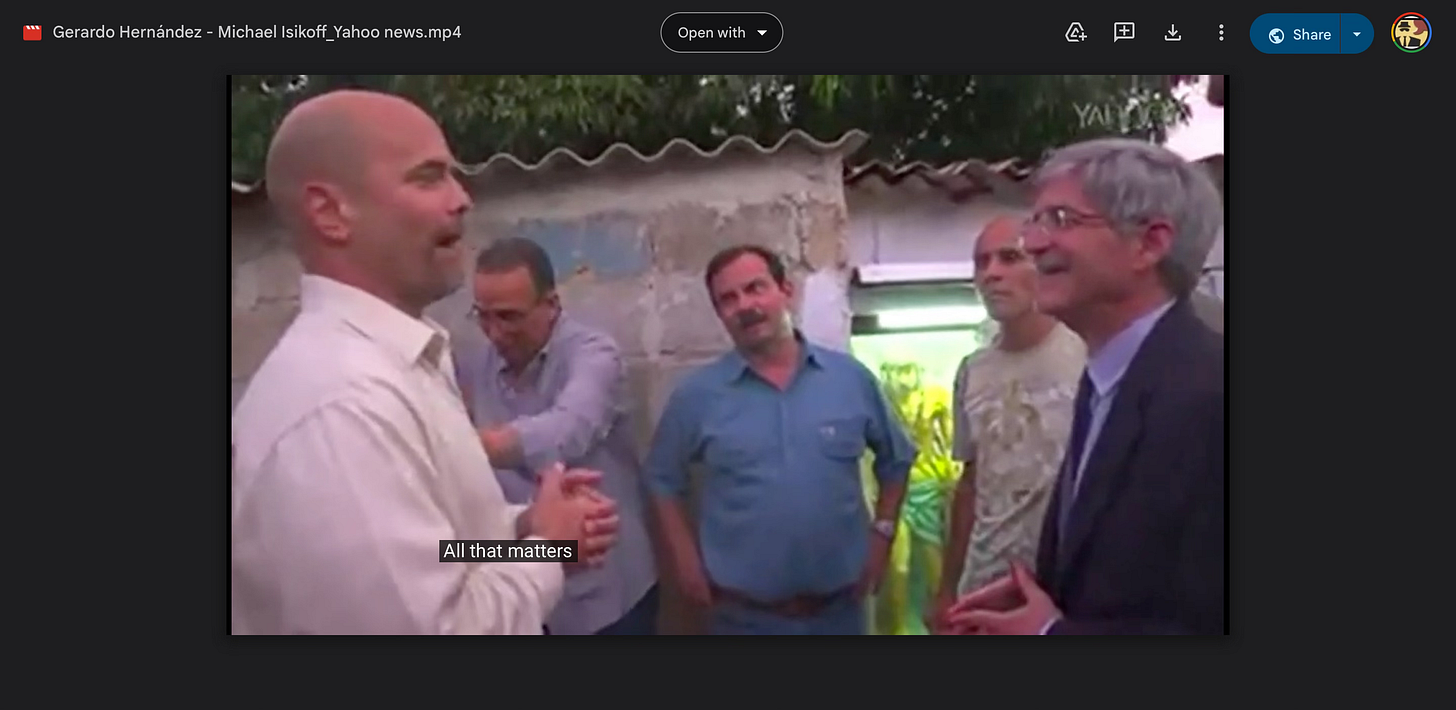

As they walked through the streets of Romerillo, one of Havana’’s poorest neighborhoods, Hernández and his Cuban 5 comrades were mobbed. It was instantly clear they had become symbols of national pride and, so it seemed then, harbingers of a new dawn in U.S.-Cuba relations. Women embraced and kissed them. Children beseeched them for their autographs, and everyone wanted a picture taken with them. There was, for Hernández, only one word to describe what was happening. It was a “miracle,” he told me that night, laughing, as much at the irony coming from him, a loyal Fidelista, as he looked up at a shrine to San Lazaro, the patron saint of Cuba.

The inside story of that U.S.-Cuba spy swap—and the fleeting moment it seemed to offer for a rapprochement between two bitter adversaries—is told with fascinating new details in I Spy: The U,S,, Cuba and the Secret Deal that Ended the Cold War, an eight-part podcast on Audible produced and narrated by Dan Ephron, executive editor of Foreign Policy. It’s an engrossing drama filled with twists and turns, crushing setbacks and high level interventions (from the Vatican, of all places) that nonetheless shows the possibilities of creative diplomacy when pursued by a White House committed to breaking loose from what it saw as dead-end policies and stale Cold War shibboleths.

But it’s also, from today’s perspective, a depressing period piece. The secret deal did not end the Cold War between the U.S. and Cuba, not even close. The widespread hopes for a new era—people to people exchanges, families reunited, an influx of U.S. tourists to Cuba, the construction of new hotels and restaurants with a surge of American investment on the island—were slammed shut in January 2017 when a new president, Donald J. Trump, committed to reversing every one of Obama’s policies, took office. Reports of strange illnesses among American diplomats and spies in the country—“Havana Syndrome,” it was called, although there was no evidence Cuba had anything to do with it—made the job easier, giving Trump grounds for all but emptying out the newly staffed U.S. Embassy.

And hardliners in Cuba didn’t help things: When political and economic protests swept the island in the summer of 2021, the Cuban government, under its new president, Miguel Diaz-Canel, cracked down in police-state fashion, locking up hundreds of demonstrators. Whatever incentive Biden administration officials might have had to restore Obama’s Cuba policy melted away and the subject all but vanished from public dialogue.

Cold Peace

Today, the U.S. embargo remains firmly in place, and Cuba is a basket case, its economy wracked by shortages and repeated power outages. Hernández, for his part, retains his high level celebrity status: He currently serves as national coordinator of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, a network of neighborhood watch committees that keep a careful lookout for signs of dissent. But while the master spy may have returned home to a hero’s welcome, in the last 18 months alone, more than a million of his fellow Cubans—a staggering nine percent of the country’s population—have given up hope and deserted the island.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Ephron tells me on the SpyTalk podcast. “There was a manifestation of hope in those first couple of years…I think it’s a story of diplomatic accomplishment that lasted long enough for us to take note and go back and even celebrate. But yeah, it’s a story of when the wheel turns and a new administration is bent on undoing the accomplishments of its predecessor.”

Still, it is a story worth telling, if only to understand what could have been and, Ephron posits, might yet be. He begins it with the painful personal ordeal of Alan Gross.

A gentle, engaging man from Bethesda, Md., the leafy Washington, D.C.suburb, who had spent years working on worthy economic development programs around the world, Gross was contacted out of the blue in 2008 by a Beltway company looking to hire him for a U.S. Agency for International Development contract in Cuba. The goal: to design a pilot project to spread the Internet to communities in Cuba.

To Gross, at first, this sounded harmless: Who could object to the Cubans getting ready access to the wonders of the worldwide web? Gross, who is Jewish, decided to focus his efforts first on Cuba’s tiny Jewish community, 1,500 strong, whose leaders were eager to download hard to find readings and prayers from the Torah and Talmud.

But as Ephron points out, there were red flags all over the place. This was still the Bush administration. An unyielding belief in the virtues of regime change was very much built into its DNA. Ephron quotes from a USAID document that laid out the underlying purpose of the Cuban Internet project. It talked about hastening the transition to a “democratic, market-oriented society.” Even more basically, it referred to “breaking the information blockade”— that is, the Cuban government’s blockade on the free flow of information. Worthy goals, to be sure. But access to the Internet in Cuba is tightly restricted. How were Cuban authorities likely to view an American like Gross traversing their country with a laptop, a cell phone and a small mobile satellite terminal, known as a BGAN—a device designed to provide unrestricted access to the Internet?

There was never any explicit talk about overthrowing the government, Gross told Ephron during one of multiple interviews he gave for the I Spy series. “But I should have known better. You know, hindsight is 20/20. I should have known better.”

Sure enough, on what was supposed to be his last night in the country, Cuban agents burst into his hotel room, grabbed him, cuffed him and took him away for aggressive interrogations aimed at getting him to confess he was an American spy. Gross, who had no training as an intelligence officer, was horrified— and scared as he realized just how serious they were.

“What was going through my head was, I’m fucked,” he told Ephron. At first, he thought the U.S. government would somehow rescue him in a matter of weeks. “And when they didn’t come, I felt I was in really deep shit,” he says.

He was indeed. Fourteen months later, in March 2011, Gross was convicted of participating in a “subversive project of the U.S. government that aimed to destroy the Revolution through the use of communication systems out of the control of authorities.” He was sentenced to 15 years in prison. In the meantime, he had lost 70 pounds and was becoming increasingly depressed, and over time, suicidal. His desperate plight started to get high level attention in Washington—from the White House and members of Congress.

But the Cubans had their own card to play: the Cuban 5.

Jailhouse Interview

It’s at this point, I have a small cameo in the story. At the time I was an investigative correspondent for NBC News. My network colleague, chief foreign affairs correspondent Andrea Mitchell, had been talking to the Cubans about Gross’s dire situation. One of them mentioned it might be a good idea if NBC were to interview Hernández, the leader of the Cuban 5. It was, of course, their ploy to plant the seeds for a potential spy swap. Hernández was holed up in a medium-security penitentiary in Victorville, Calif., a remote town north of the San Bernardino Mountains, about 90 miles east of Los Angeles. Flying across the country and trekking an hour and a half to get to a federal prison was not exactly a glamorous assignment and Mitchell had other matters to attend to. She suggested I go instead.

I did. And the interview with this veteran Cuban spy was not exactly what I expected. He may have been a master spy, but Hernández, sporting a neatly trimmed goatee, was easy-going, engaging and chatty, with a hearty laugh; despite his own seemingly hopeless double life sentence, he seemed curiously unperturbed by the exceedingly low chance that he would ever get out. He presented the Cuban perspective on his predicament: He and his four Cuban intelligence officer colleagues had been dispatched years earlier not to spy on the U.S. government— although at least one of them had landed a job on a U.S. military base — but to keep an eye on anti-Castro groups in Florida who had historically engaged in notorious acts of terrorism against Cuba: the bombing of a Cubana Airlines flight in 1976 that killed 73 passengers (including the entire Cuban national fencing team) and a series of hotel bombings in the 1990s aimed at disrupting the island’s tourist industry.

“We came here with fake passports, fake identities,” he told me, implicitly confessing to many of the charges against him. But, he added, “we act out of necessity.” Unlike the United States, "Cuba doesn’t have drones to neutralize the terrorists abroad," said Hernández. "They need to send people to gather information and protect the Cuban people from these terrorist actions.”

Hernández did dispute the most serious charge against him: that as a result of his spying, he was complicit in murder when he tipped off his handlers in Havana to upcoming flights of Brothers to the Rescue, an anti-Castro exile group led by a Bay of Pigs veteran, Jose Basulto, that were flying into Cuban airspace dropping anti-regime leaflets. With Hernández’ coded heads up, a Cuban fighter jet shot down two of the Brothers to the Rescue flights in Feb. 1996, killing four men. In late 2011, a jury in Miami, where anti-Castro sentiments ran hot, convicted him of conspiracy to commit murder, triggering his double life sentence although Hernández insisted he had no idea that the planes would be lethally targeted.

Any regrets? I asked him. “I regret that I got caught,” he said.

Some weeks later, I was in Havana to do pieces for NBC’s Nightly News and the Today show on the plight of Alan Gross. I included some audio clips from my interview with Hernández, the first one on his case, and Cuba’s demand for his release as the price for Gross’s freedom, was presented to a national audience. (“Is there a U.S.-Cuba Spy Swap in the Works?” read the chyron on my Today show piece.) I also included another emotional interview I did in Havana that may have had an even bigger impact. His wife Adriana, then 43, choked up as she told me about how much she missed her husband— and her desperate desire to have his baby.

"Every detail, every single moment reminds me of him," she said. “There is a woman here suffering.” Although I had no idea at the time, her teary eyed plea would soon lead to a completely out of the box move to resolve the U.S.-Cuba logjam—one that veteran diplomats never dreamed of.

Sperm Diplomacy

Not long after my pieces ran on NBC, Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and one of his chief aides, Tim Reiser, were in Havana, the latest in a parade of lawmakers and staffers trekking to Cuba to press for Gross’ release. “And they meet with Adriana much the way you met with Adriana,” Ephron tells me. “And this pitch [to have a baby] really resonates with Leahy and Leahy’s wife who is there and with Rieser. And they go back to the United States and set about trying to make it happen. This isn’t a swap, this isn’t the deal itself, but what can the United States do for Adriana and Gerardo in this endeavor for her to have a child?”

Rieser, a seasoned Washington operator, began pressing the Bureau of Prisons to help Adriana get pregnant through artificial insemination, arguing it would build goodwill with the Cubans and could lead to Gross’ release.

It’s fair to say prison officials were nonplussed by the inquiry. For their part, State Department officials were near apoplectic. Roberta Jacobson, then the assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere Affairs, tells Ephron she thought the idea was “pretty outrageous” when she first got wind of it. “Let’s just say that I or anybody at the State Department says, ‘Yeah,‘we want to do this,’” Jacobson says on I Spy. “How are we going to defend doing something so absolutely unprecedented? This is going to be a huge political issue with the Florida delegation, with the New Jersey delegation that is Cuban American. [Sen. Robert Menendez, an anti-Castro hardliner from New Jersey, had just become chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.] How are we going to defend this publicly?”

But Rieser kept at it.and eventually his boss, Leahy, talked to Attorney General Eric Holder and got him to sign off. Later in 2013, prison officials in Victorville cleared out their health clinic, brought in Hernández and gave him a small plastic cup to deposit his sperm. After he did so, “I saw the doctor taking it and I asked him, ‘Hey, where are you taking this? Your car?’” said Hernández, recalling the moment for Ephron in I Spy. In fact, a doctor from a fertility clinic in Panama — where Adriana had frozen her eggs— arrived at the prison and picked up the sperm and flew it back to Panama. By early 2014, Adriana was pregnant.

All this was kept entirely secret — by both the Americans and the Cubans (who made sure Adriana stayed out of public view lest onlookers get curious about how the wife of a spy who had been locked up for 14 years could be with child.) Both sides feared that if their respective publics got wind of what was going on, their own hardliners would go ballistic and sabotage any deals. But there was something else going on then that the public knew nothing about: secret negotiations between Cuba and the United States aimed at a diplomatic breakthrough much bigger than a simple spy swap.

So secret, in fact, that even Jacobson and the rest of the State Department knew nothing about it.

Secret Talks

In early 2013, President Obama had convened a meeting of his senior staff in the White House Situation Room to discuss new initiatives for his second term. Cuba was towards the top of the list. The Democratic president had long thought that the U.S.’s rigid anti-Cuba policies— an economic embargo, harsh sanctions, no diplomatic relations, branding it a terrorist state— was pointless, having made no dent in the regime’s grip on power for the past half century. He wanted to open up a backchannel to Havana — with somebody close to him doing the negotiating— so the Cubans understood this was serious. Who wants to take charge of Cuba? he asked his staff. Ben Rhodes raised his hand.

Rhodes was Obama’s speechwriter and “strategic” communications advisor on national security matters. Then 35, with no diplomatic experience (his degree was a master of fine arts in creative writing) he comes off as a character straight out of Aaron Sorkin’s The West Wing— a glib, wise to the ways of Washington exterior masking the inner core of an earnest do-gooder. “Change will not come if we wait for some other person…We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.” Obama had said those words. Rhodes had written them.

So by mid-2013, while the Alan Gross drama was playing out in Havana, Rhodes and a National Security Council colleague, Ricardo Zuniga, were in a highly secure facility in the Canadian woods over an hour outside of Ottawa. Across the table was a garrulous Cuban princeling, a former military officer who had lost an eye fighting in Angola, Alejandro Castro, son of Raul and nephew of Fidel.

True to his family heritage, Alejandro Castro was prone to lengthy speechifying about the perfidy of the United States. Early on in the Canada talks, he launched into a tirade about America’s efforts to crush the Cuban revolution, assassinate his uncle and target the island with spies and saboteurs. Rather than rise to the bait, Rhodes chose shrewd deflection.

“So when he was done, I made a point of kind of pushing my talking points away from in front of me,” Rhodes recalls in I Spy. ”Like I, I understand that that history is, like, really important to you. I’m sure that I could take issue with some of it and some of it’s true. Which I think probably U.S. officials don’t normally say. But I wasn’t even born when some of this stuff happened. And [Castro] laughed at that. And I was like, ‘I’m here because I work for Barack Obama.’ And he wasn’t even born when some of this stuff happened. And he certainly wants to get past it. That’s why I’m here.”

His somewhat disarming candor — and perhaps even more, his acknowledgement that at least some of Cuba’s allegations against the United States were actually “true”- made a difference. The ice was broken. Before long, they adjourned for lunch and Castro and Rhodes, over sandwiches, talked baseball. .

There was still much to negotiate and hard sledding ahead. Rhodes knew there was a problem with the spy swap part of the deal. Giving up Hernández was tough enough for the administration. But the real problem was the Americans couldn’t trade him and the other two members of the Cuban 5 for Gross in a spy swap because, as far as the U.S. was concerned, Gross was not a spy. Rhodes and Obama needed a bigger fish — and there was an obvious candidate, Rolando Sarraff Trujillo. He had been an officer in the cryptology section of Cuba’s Directorate of Intelligence who at some point, had been turned by the CIA and became the agency’s top mole before he was arrested in 1995. How valuable had Trujillo been to the Americans? There was a symmetry to the answer. Among the Cuban spies he fingered for the CIA: Hernández and the Cuban 5. As Ephron recounts, Rhodes was candid with the Cubans, telling them in effect: “To get back your spies, to bring home your national heroes, you have to release the traitor who exposed them.”

Holy See

Ultimately, the Cubans agreed. But to overcome the years of distrust the two parties decided they needed a guarantor, and reached out to Pope Francis and the Vatican. In the end, as a “pre-rehearsal” for the grand announcement, Rhodes and his Cuban counterparts were led into a giant, beautifully decorated room in the Vatican— complete with ornate drapes and crucifixes—where they read the text of their agreement to the Cardinal who served as the Pope’s Secretary of State. When they realized that the deal was far more than a mere spy swap, but also involved the restoration of full diplomatic relations, the Cardinal and his top aides were, according to Rhodes, “in tears.”

From my narrow perspective, the world-shattering news announced by Obama and Raul Castro in December 2014 also led to a bit of a journalistic mini-coup. Gerardo flew home to be greeted by a joyous Adriana, nine months pregnant. Two weeks later, their baby, Gema (Spanish for precious stone) was born. The Cubans were bombarded with requests to interview the man whose baby had helped end the U.S.-Cuba Cold War. In mid-February, I got word. He would give me the exclusive.

“I told them I wanted to give my first interview to the guy who came to see me in prison,” he told me as I met him, Adriana and one month old Gema in a Foreign Ministry safe house attended by a legion of nannies, cooks and servers. He was as engaging as ever. Asked to contrast his new life back home in Cuba with his past life in federal prison, he nodded to a formidable woman hovering in the background: “I have a new warden now,” he said. “My mother-in-law.” But there was no doubt about his loyalties. “What I’m telling you right now, I already told Raúl Castro: I’m a soldier,” said Hernández, pounding his chest. “I’m ready to receive my next order.”

The saddest part of I Spy is the aftermath. However exciting the early days of the U.S.-Cuba deal (who even remembers Obama flying to Cuba in March, 2016 and attending a baseball game with Raul Castro?) the unravelling of the relationship is painful to revisit. It wasn’t just Trump who upended everything. Cuba’s militant hardliners were suspicious from the start, encouraged by a 90-year-old Fidel who denounced Obama in the party newspaper as “the same dog with a different color.”

For all this, Ephron still sees in the story a glimmer of hope. The spy swap saga is a tale of “what might have been yes, but it is also a story of what could be. Because if the two sides could do it once, if they could get together and negotiate an agreement and get past a long history of enmity, they can do it again. There just needs to be leadership on both sides willing to do it and goodwill.”

For that, we may have quite a wait.

You can listen to the SpyTalk podcast here, on Simplecast, or wherever your preferred platform, like Apple.

Fascinating